Primary Progressive Aphasia (PPA) is a neurodegenerative condition that gradually impairs language capabilities while other cognitive functions often remain preserved for some time. The early stages offer a critical window to understand the prognosis and to implement practical home-based strategies. This article details common early signs, the timeline of progression, and evidence-based speech and language activities that caregivers and people with aphasia can use at home to support communication, memory, and connection.

Understanding Primary Progressive Aphasia and Early Signs

Most people associate aphasia with a sudden event. A stroke occurs, or a head injury happens, and communication changes instantly. Primary Progressive Aphasia (PPA) is fundamentally different. It is a neurodegenerative condition, meaning it begins subtly and evolves over time. It is caused by the gradual loss of brain cells in the specific areas of the brain that control language.

Unlike Alzheimer’s disease, where memory loss is usually the first red flag, people with PPA often keep their memory, personality, and reasoning skills intact during the early years. The primary struggle is strictly with language—speaking, understanding, reading, or writing. Because it is rare, affecting roughly 3 to 4 people per 100,000, it is frequently misunderstood or misdiagnosed initially.

It is also important to understand the biological cause. PPA is driven by physical changes in the brain, usually resulting from Frontotemporal Degeneration (FTD) or, less commonly, Alzheimer’s disease pathology. Research indicates that specific proteins build up in the brain, causing cell loss in language centers. It is a biological condition, not a result of stress, diet, or past lifestyle choices.

The Three Main Variants of PPA

PPA is not a uniform experience. It generally falls into three distinct categories, or “variants.” Identifying the specific type is essential because symptoms and management strategies differ for each.

Nonfluent/Agrammatic Variant (nfvPPA)

This form is characterized by effortful speech. The person knows what they want to say, but producing the words feels like a physical struggle. Speech often becomes choppy or hesitant. Grammar may deteriorate; the person might omit small connecting words like “the,” “is,” or “and,” speaking in short bursts similar to a telegram. There can also be apraxia of speech, a motor planning issue where the mouth struggles to form the correct sounds.

Semantic Variant (svPPA)

In this variant, the mechanics of speech remain smooth. The person speaks fluently and grammatically correctly, but the words lose their meaning. This represents a loss of “object knowledge.” A person might look at a common object, like a toaster, and not only forget the word “toaster” but also forget the appliance’s function. They might ask, “What is a key?” when holding one. You might hear them use vague words like “thing” or “stuff” frequently, or substitute a general category for a specific item, like calling a dog an “animal.”

Logopenic Variant (lvPPA)

This type is often associated with underlying Alzheimer’s pathology but presents as a language issue first. The hallmark is word-finding pauses. The person speaks slowly because they are constantly searching for the right word. They might get stuck on a sentence, pause for a long time, or substitute sounds (like saying “gat” instead of “cat”). Repetition is also difficult; if you say a long sentence and ask them to repeat it back, they often cannot retain the full sequence.

Recognizing the Early Signs and Timeline

The timeline for PPA is variable, but it is generally considered a younger-onset condition compared to other dementias. Symptoms often begin in the 50s or 60s, though onset can occur later. Because the decline is gradual, families often look back and realize symptoms were present for a year or two before they sought medical help.

Common First Concerns

Families usually report subtle changes first. It might be a conversation at dinner where the person stops mid-sentence, unable to retrieve a name they have known for decades. Or perhaps they start using the wrong words that sound similar, like saying “knife” instead of “wife,” or words that are related in meaning, like “cutter” instead of “knife.”

| Feature | Typical Early Presentation |

|---|---|

| Speech Rate | Slower, with frequent pauses to search for words. |

| Comprehension | Generally good for casual conversation, but complex sentences may be confusing. |

| Social Skills | Usually preserved early on, though the person may withdraw due to embarrassment. |

| Memory | Episodic memory (remembering events) remains strong in the first few years. |

Behavioral and Cognitive Changes

While language is the primary deficit for the first two years, other changes can eventually emerge. In the semantic variant specifically, families might notice behavioral shifts earlier than in other types. This can look like a lack of empathy, rigid routines, or changes in food preferences, such as a sudden craving for sweets. However, for most PPA cases, significant cognitive decline outside of language usually does not develop until later in the disease course.

Getting a Diagnosis

Diagnosing PPA can be frustratingly slow. The average delay between the first symptom and a confirmed diagnosis is often around three years. It requires a team approach to rule out other causes like a stroke or a tumor.

The process typically involves a speech-language evaluation to test naming, grammar, and comprehension. A neuropsychological exam helps confirm that memory and other thinking skills are relatively preserved, which distinguishes PPA from typical Alzheimer’s disease. Brain imaging, such as an MRI or an FDG-PET scan, is used to look for specific patterns of atrophy (shrinkage) or low activity in the language centers of the brain.

Primary Progressive Aphasia is a challenging diagnosis, but identifying it early is valuable. It allows the person and their family to stop wondering “what is wrong” and start planning.

Why Early Recognition Matters

Spotting these signs early changes how you manage daily life. Since PPA is progressive, the goal isn’t “curing” the language loss but preserving communication for as long as possible.

When you know what you are dealing with, you can begin “banking” voice messages or creating communication boards while the person can still participate in making them. It also opens the door to legal and financial planning while the person still has the competency to make their own decisions. Understanding that the hesitation in speech is a medical condition, not just “getting old” or “not trying hard enough,” reduces frustration for everyone in the house.

Primary Progressive Aphasia – StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf notes that early intervention can improve outcomes for both patients and caregivers. By adjusting expectations and environment early, families can maintain a connection even as words become harder to find.

How PPA Progresses and What Families Can Expect

Receiving a diagnosis of Primary Progressive Aphasia (PPA) shifts the ground beneath a family’s feet. Unlike a stroke, where the damage happens at once and recovery begins immediately, PPA is a journey of gradual change. Understanding how this condition moves forward helps you prepare for the road ahead without getting lost in the fear of the unknown.

The Path of Progression

PPA is unique because it targets language first. For at least the first two years, speech and language difficulties are typically the only major symptoms. Memory, personality, and the ability to navigate physical spaces usually remain intact during this initial window. This preservation of other skills can be confusing for friends and extended family who see a person acting “normal” but struggling to find a specific word or finish a sentence.

However, the decline is steady. The specific variant—whether nonfluent, semantic, or logopenic—dictates how the early years look, but the progression often follows a broadening pattern.

Spreading to Other Language Domains

Initially, the struggle might be just speaking or finding words. Over months and years, these deficits bleed into other areas of communication. A person who could read the newspaper but not speak clearly might eventually find the words on the page losing their meaning. Writing often declines alongside speech. You might notice emails becoming shorter, containing more spelling errors, or lacking grammatical structure. This is known as dysgraphia and dyslexia, and it makes text-based communication increasingly difficult over time.

The Shift to Non-Language Symptoms

While language is the primary issue, PPA is a neurodegenerative condition. As the underlying changes in the brain spread, other cognitive and physical challenges can emerge. Research suggests that broader cognitive or behavioral impairments often develop later, sometimes not until 8 to 12 years after the first symptoms appear. However, this varies significantly.

- Movement and Motor Skills: Some individuals, particularly those with the nonfluent variant, may develop stiffness, slowness, or balance issues similar to Parkinson’s disease. Data indicates that roughly 40% of patients may develop parkinsonism, sometimes within a few years of symptom onset.

- Behavioral Changes: In the semantic variant, changes in personality can occur in the mid-to-late stages. You might notice a lack of empathy, rigid routines, or even changes in food preferences.

- Memory Issues: While episodic memory (remembering what you did yesterday) is usually preserved early on, short-term memory issues can creep in as the condition advances, often overlapping with symptoms seen in Alzheimer’s disease.

Functional Impact on Daily Life

The slow progression allows for adaptation, but it also requires constant adjustment. Because the onset is often in the 50s or 60s, many people are still working, driving, and managing households when symptoms begin.

Employment and Social Roles

Work is often the first area to suffer. Subtle word-finding pauses or trouble understanding complex instructions can be mistaken for stress or fatigue. As communication becomes harder, maintaining a job that requires phone calls, meetings, or quick decision-making becomes unsustainable. This loss of professional identity can lead to depression, which is a significant risk for both the person with PPA and their family.

Driving and Independence

Driving is a complex issue. Physical ability to drive often outlasts the ability to communicate. However, reading road signs, understanding traffic updates, or reacting to emergency commands requires language processing. Regular assessments are necessary. Independence in other areas, like managing finances or medications, will also decline. Numbers can become just as confusing as words, leading to errors in checkbooks or dosage mistakes.

Planning for the Future

Since PPA is progressive, the window for the person with the diagnosis to participate in their own planning is limited. Taking action early gives them a voice in their future care.

Legal and Financial Safety Nets

Do not wait until communication is lost to handle paperwork. Establishing a durable power of attorney for both finances and healthcare is critical. It allows a trusted family member to step in when the person can no longer express their wishes or understand complex contracts. Discussing long-term care preferences now—while conversation is still possible—removes the burden of guessing later.

Building a Care Team

You cannot manage this alone. A strong care team typically includes a neurologist for medical management, a speech-language pathologist (SLP) for communication strategies, and a social worker or counselor to help navigate the emotional toll. Connecting with support groups is equally vital. Knowing you aren’t the only family dealing with this specific, rare diagnosis provides immense relief.

Treatment and Monitoring

It is important to be honest about the medical reality: as of late 2025, there is no cure for PPA that stops the disease in its tracks. Disease-modifying treatments are limited. However, this does not mean there is nothing to do.

Therapy as Maintenance

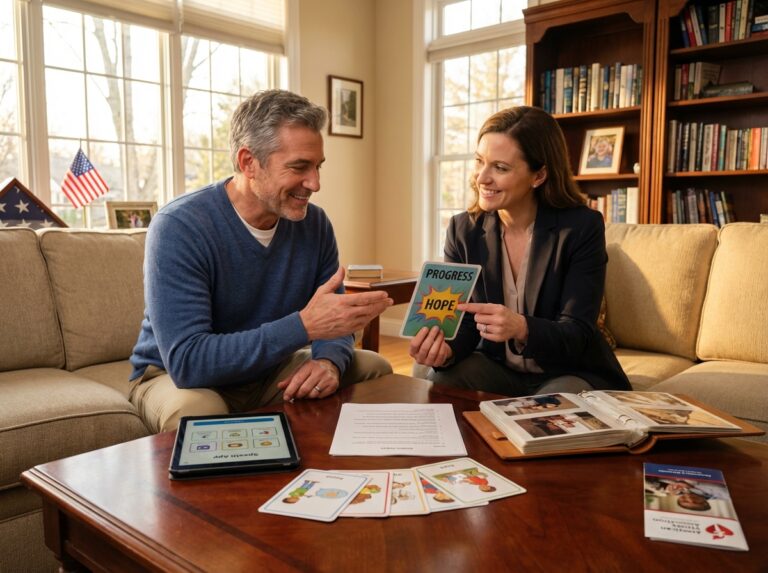

Speech therapy in PPA is different from stroke recovery. The goal isn’t necessarily to “fix” the broken language but to preserve skills for as long as possible and develop compensatory strategies. Primary progressive aphasia management focuses on maximizing quality of life. This might involve creating communication wallets with pictures, practicing scripts for common scenarios, or training the family on how to support conversation.

When to Consult Professionals

Monitoring changes is a continuous process. You don’t need to run to the doctor for every stumbled word, but you should track significant shifts. Consult your neurologist or SLP if you notice:

- Sudden, rapid decline (PPA is usually slow; sudden changes could indicate a different medical issue like an infection).

- New difficulty with swallowing or choking on food.

- Falls or significant changes in walking ability.

- Major behavioral shifts, such as aggression or wandering.

Tools like the Montreal-Toulouse Language Assessment Battery (MTL-BR) are sometimes used by professionals to detect early signs and monitor progression, helping to tailor therapy to the specific deficits appearing at that time.

The timeline of PPA is unpredictable. Some people live with the condition for many years with a slow decline, while others progress more quickly. The most effective approach is to focus on what is possible today while quietly preparing for tomorrow. By setting up the right support systems early, you allow the person with PPA to remain connected to their life and loved ones for as long as possible.

Practical Home Practice Strategies for Speech and Language

Building a consistent home practice routine helps maintain language skills for as long as possible. These exercises work best when adapted to personal interests and current abilities. The goal is not perfection. The goal is keeping the neural pathways active through repetition and meaningful use.

Word Retrieval and Naming Exercises

Finding the right word is often the first challenge. Instead of forcing the word out, use strategies that strengthen the connections around the word.

Semantic Feature Analysis (SFA)

This technique helps you describe a word when you cannot name it. Do not just look at a picture and guess. Describe the object using five specific questions. What group does it belong to? What do you use it for? What does it look like? Where do you find it? What does it remind you of? This process strengthens the semantic network in the brain.

Cueing Hierarchies

Partners can help by giving clues in a specific order. Start with a description. If that fails, give the first sound. If that fails, say the word and have the person repeat it. This is better than letting someone struggle in silence. It keeps the conversation moving and reduces frustration.

Errorless Learning

This approach prevents the brain from practicing mistakes. If you do not know a word, the partner provides it immediately. You then repeat the correct word three times. This builds correct neural patterns rather than reinforcing the error.

Phrase and Sentence Production

Moving from single words to sentences requires practice. These activities focus on functional communication for daily needs.

Script Training

Create short scripts for common situations. You might write a script for ordering coffee or answering the phone. Practice these exact phrases every day until they become automatic. Start with three short sentences. Read them aloud together, then fade your voice out until the person can say them alone.

Sentence Completion

The partner starts a familiar phrase, and the person with aphasia finishes it. Use common idioms or song lyrics. Examples include “salt and…” or “up and…” This taps into automatic speech reserves which often remain intact longer than voluntary speech.

Recasting

When the person speaks with errors, the partner repeats the idea back using correct grammar. Do not correct them explicitly. Just model the right way. If they say “Store go me,” you say “Yes, you are going to the store.”

Fluency and Motor Speech Support

For those with nonfluent variant PPA or apraxia, the physical production of speech is difficult. Rhythm and pacing can help.

Melodic Intonation

Intonation uses the right side of the brain to support the left side. Turn simple phrases into a hum or a melody. Hum the pattern of “I love you” or “Water please.” Gradually add the words back into the melody. This bypasses some motor planning blocks.

Pacing Techniques

Use a pacing board or simply tap a finger on the table for each syllable. This slows down speech and gives the brain time to plan the next sound. It improves intelligibility for people who speak too fast or stumble over complex words.

Comprehension and Reading Exercises

Understanding language requires active engagement. Passive listening is often not enough to maintain skills.

Guided Reading

Read short paragraphs of high interest. Use simplified news articles or hobby magazines. After reading, answer three specific questions. Who was the story about? What happened? Where did it take place? Underline the answers in the text to reinforce the connection.

Answering Wh- Questions

Practice answering who, what, where, and when questions during daily activities. While cooking, ask “What are we cutting?” or “Where does the pan go?” This keeps language processing active in real-time situations.

Reading and Writing Supports

Writing helps reinforce reading and speaking. Even if handwriting is difficult, the motor act of writing can boost memory.

Copy and Trace

Write out functional words like family names, address, or grocery items. Have the person trace over the letters and then copy them below. This connects the visual shape of the word with the motor movement.

Personalized Labeling

Place labels on common items around the house. Seeing the word “fridge” every time you walk by it provides constant, passive reading practice. Update these labels or move them to different rooms to keep the brain noticing them.

Memory and Multimodal Cues

Since Primary Progressive Aphasia affects language first, using other brain systems supports communication.

Spaced Retrieval

This memory training helps retain important information. Ask a question like “What is my name?” Provide the answer immediately. Ask again in 15 seconds. Then ask in 30 seconds, then one minute. If they get it wrong, give the answer and start the time over. This builds retention over expanding intervals.

Multimodal Communication

Encourage the use of gestures, drawing, and pointing. If a word is stuck, draw it. If you cannot say “drink,” make a drinking motion. This is not “cheating.” It is effective communication. It takes the pressure off the verbal system.

Sample Daily Routine and Weekly Plan

Consistency beats intensity. A short session every day is better than a long session once a week.

Daily 20-Minute Routine

Spend 5 minutes on a warm-up like singing a familiar song or automatic counting. Spend 10 minutes on a specific task like script training or naming family photos. Finish with 5 minutes of a success activity, something they can do easily to end on a high note.

Weekly Schedule Idea

Monday and Wednesday focus on word retrieval and naming. Tuesday and Thursday focus on reading and writing scripts. Friday is for functional role-play like practicing a phone call. The weekend can be for casual conversation practice without pressure.

Supporting Memory Social Connection and Daily Communication

Language drills and speech exercises are important, but they don’t always translate perfectly to the dinner table or a chat with a neighbor. When you are living with Primary Progressive Aphasia (PPA), the goal shifts from “fixing” the speech to maintaining the connection. We want to keep the person involved in daily life for as long as possible. This requires a different set of tools that focus on the environment, the communication partner, and using technology to fill the gaps.

Changing How You Speak

The most effective tool in your house is often the communication partner. You can change your habits easier than the person with PPA can change theirs. Small adjustments in how you ask questions or present information can stop frustration before it starts.

Slow down and pause

We often speak too fast without realizing it. Slow your rate of speech slightly, but keep your tone natural. Do not speak like you are talking to a child. Add pauses between sentences to let the person process what you said. Silence is okay. It gives their brain a chance to catch up.

Use supported turns

Avoid open-ended questions like “What do you want for dinner?” These require retrieving specific words, which is difficult. Instead, offer choices. Ask, “Do you want chicken or pasta?” If that is too hard, show the actual items. This takes the pressure off word retrieval and keeps the conversation moving.

Verify and clarify

If you think you understood, check. Say, “I think you said you want to go to the park, is that right?” This validates their effort. If you don’t understand, admit it. Say, “I missed that last part, can you tell me again?” Blame your ears, not their speech.

Modifying the Home Environment

Your home setup can either support communication or make it harder. PPA often comes with sensitivity to noise or difficulty filtering out distractions. A few physical changes can reduce cognitive load.

Reduce background noise

Turn off the TV or radio during conversations. Background noise competes for attention. If you are having a serious discussion, sit face-to-face in a quiet room. Good lighting helps too, as seeing your facial expressions provides extra context cues.

Label key areas

As the condition progresses, finding things becomes harder. Place simple labels on drawers or cupboards. You can use words or photos. A picture of socks on the sock drawer or a label saying “Coffee Mugs” on the cabinet helps maintain independence. Keep common items in the same place every day.

Visuals and Conversation Tools

When words fail, visuals step in. You don’t need to wait until speech is gone to use these. Introducing them early helps the person get used to them while they still have good cognitive flexibility.

Topic boards

Keep a small whiteboard or a printed sheet with common topics (family, food, bathroom, pain, feelings) in the living room. If the person gets stuck, they can point to the general topic. This narrows down the guessing game significantly.

Conversation books

Create a small photo album or a digital folder on a tablet. Fill it with photos of family members, pets, past vacations, or hobbies. Label them clearly. This allows the person to share stories or answer questions by pointing to a picture rather than struggling to find a name.

Technology and AAC Options

Technology has advanced significantly by 2025. Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) is not just for late stages. Using it early can preserve autonomy.

Voice banking

This is best done as early as possible. Voice banking allows a person to record specific phrases or create a synthesized version of their own voice. Later, they can type messages that sound like them, not a robot. It preserves a sense of identity.

Text-to-speech apps

Simple apps on a phone or tablet can speak typed text. Many people with PPA retain the ability to type or select icons longer than they can speak. Primary Progressive Aphasia affects language access, so having a backup output method reduces anxiety.

Meaningful Activities

Connection isn’t just about talking. It is about sharing an experience. Since memory for events often remains intact longer in PPA compared to Alzheimer’s, you can leverage this for social interaction.

Shared reading and audiobooks

If reading becomes hard, switch to audiobooks or read aloud together. You can also use “masked” reading where you read a familiar phrase and let them finish it. This works well with poetry or famous speeches they know well.

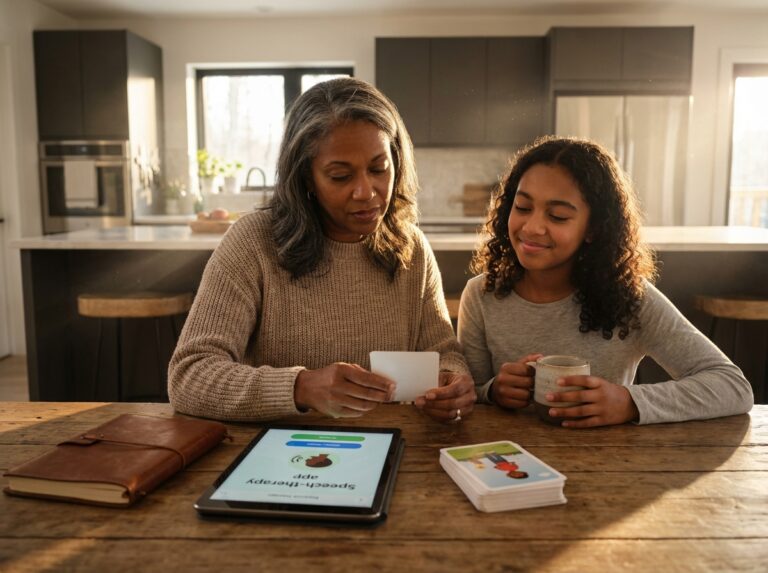

Involving children and grandchildren

Children are often intuitive and notice when something is wrong. It is better to be honest in a simple way. Explain that the person has a brain condition that makes talking hard but they still love the child. You can find activities that do not require words. Puzzles, drawing, or listening to music are great ways to connect. This removes the pressure to talk and allows the relationship to continue. Creating a “memory box” with items the child and the grandparent can look at together allows the child to do the talking while the grandparent enjoys the shared attention.

Music and memory

Music is processed in a different part of the brain than language. Many people with aphasia can sing words they cannot speak. Create playlists of their favorite songs from their 20s. Sing along together. It lifts the mood and provides a successful verbal experience.

Caregiver Wellbeing and Support

You cannot pour from an empty cup. Research shows that caregivers for PPA are often younger than those for Alzheimer’s, often balancing work and children. The emotional toll is heavy.

Handling frustration

Frustration is a natural reaction to losing the ability to speak. It is not a behavioral problem but a response to a difficult situation. The best approach is to acknowledge the frustration openly. You can say “I know this is hard” or “I can see you are stuck.” Take a break from the conversation if the tension gets too high. Pushing through the frustration usually leads to more errors. Establishing a “time out” hand signal can help; if either the person with PPA or the caregiver uses it, both stop talking for a few minutes without guilt.

Find your community

PPA is rare, so your neighbor might not understand. Look for specific PPA support groups. Organizations like the National Aphasia Association or local university clinics often host these. Connecting with peers who understand the specific frustrations of PPA is vital.

Respite is necessary

Burnout is a real risk. Schedule time where you are not the primary communicator. This might mean hiring a companion who understands aphasia or asking a family member to take over for a few hours. You need quiet time to recharge your own patience.

Professional help

Speech therapy isn’t just for the patient. A speech-language pathologist can train family members on specific cueing techniques. Primary Progressive Aphasia – StatPearls notes that early intervention improves outcomes for both the patient and the caregiver. Don’t hesitate to ask for a “communication partner training” session.

Key Takeaways and Next Steps

We have covered a lot of ground regarding Primary Progressive Aphasia. You now understand that this condition is distinct from the sudden aphasia seen after a stroke. It is a neurodegenerative condition where language skills change gradually. The information might feel heavy right now. That is a normal reaction. The goal of this chapter is to organize those thoughts into a clear path forward. You do not need to do everything at once. You just need to know where to place your feet next.

Core Principles to Remember

There are three main concepts that should guide your approach to life with PPA. Keeping these in mind will help you filter through advice that might not apply to your specific situation.

Early recognition changes outcomes

Research shows that early intervention can slow the progression of symptoms and maintain communication skills for longer. Since language is the primary deficit for the first two years in most cases, you have a window to build strategies before other cognitive changes might appear.

The type of PPA dictates the strategy

We discussed the variants earlier. If you or your loved one has the nonfluent variant, your home practice will focus on motor speech and scripts. If it is the semantic variant, you will focus more on word comprehension and visual supports. Tailoring your approach prevents frustration.

Connection is more important than perfection

The goal of home practice is not to “fix” the brain or force perfect grammar. The goal is to keep participating in life. Evidence suggests that maintaining social connection and communication reduces the risk of depression, which is higher in PPA families due to the younger age of onset compared to Alzheimer’s.

Your Prioritized Action List

It helps to have a checklist. This list prioritizes the most impactful steps you can take immediately.

- Schedule a specialized speech evaluation

If you have not done this yet, it is your first step. You need a baseline. Look for a speech-language pathologist who understands neurodegenerative disorders. They might use tools like the Montreal-Toulouse Language Assessment Battery to pinpoint exactly which language areas are strong and which need support. This guides your home practice. - Establish a legal and care plan now

This is difficult but necessary. While the median age of diagnosis is often around 72 years, symptoms frequently start earlier. You want to make decisions about finances and healthcare while language skills are strongest. It gives the person with PPA a voice in their future. Do not wait until communication becomes too complex. - Start a short daily practice routine

Consistency beats intensity. Set aside 15 to 20 minutes a day for focused communication practice. This might be reviewing a photo album and naming family members or practicing a script for ordering coffee. Keep it low-stress. - Train your communication partners

A person with PPA does not communicate in a vacuum. Partners need to learn how to support conversation. This includes learning to wait longer for a response or using gestures. Research indicates that caregivers are often female and around 52 years old on average. The burden often falls on spouses who are still working. Training helps reduce that burden. - Set up visual supports immediately

Do not wait until words fail completely. Start using a communication board or a tablet app now. Getting used to these tools while comprehension is high makes them much more effective later. It acts as an insurance policy for communication. - Plan neurology follow-ups

PPA is progressive. You need a neurologist to monitor changes. About 40% of patients may develop movement issues like parkinsonism later in the disease course. Regular check-ups ensure you are managing all symptoms, not just the speech issues.

Measuring Progress and Adjusting Expectations

In stroke recovery, we look for restoration of function. In PPA, “progress” looks different. We measure success by maintenance and adaptation.

Redefine what success looks like

If you practiced a script for answering the phone and you are still doing it independently three months later, that is a huge success. If you cannot say the words but you successfully used a picture to show you wanted water, that is also a success. You are maintaining your autonomy.

Adjust routines as symptoms change

You might notice that a specific exercise becomes too frustrating. That is a sign to change the activity, not to stop communicating. If naming pictures becomes too hard, switch to matching pictures or simply pointing. Be flexible. The disease changes, so your strategies must change too.

Building Your Support Network

Isolation is a significant risk for families dealing with PPA. The condition is rare, affecting roughly 3 to 4 people per 100,000. You might feel like no one in your local community understands.

Join specialized support groups

Connecting with others who are walking the same path is vital. You can share practical tips about which apps work or how to handle frustration. Primary Progressive Aphasia resources often list support groups specifically for this condition.

Explore teletherapy options

Since PPA specialists can be rare in rural areas, teletherapy is a great equalizer. You can access experts from major medical centers without leaving your home. This is especially helpful if mobility becomes an issue later on.

Moving Forward with Purpose

Living with PPA requires courage and adaptability. It is easy to look at the statistics or the progressive nature of the condition and feel overwhelmed. Focus on today. Focus on the conversation you are having right now.

Small, consistent actions add up. Every time you use a gesture, practice a word, or use a communication board, you are fighting for connection. You are preserving the person’s ability to participate in their own life.

There is no cure yet in 2025, but there is care. There is strategy. There is a way to live well with this diagnosis. Take it one day at a time. Keep communicating in whatever way works. You have the tools to make a difference in daily life.

Sources

- Primary Progressive Aphasia – StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf — Primary progressive aphasia (PPA) refers to a group of neurodegenerative diseases in which gradual speech and language impairment are the primary presenting …

- Incidence of Primary Progressive Apraxia of Speech … – Neurology.org — The incidence of PPAOS was 0.14 persons per 100,000 person-years (95% CI 0.02–0.55 persons per 100,000), whereas for the 8 patients with PPA, …

- Primary progressive aphasia research updates – UChicago Medicine — PPA is a unique neurological condition that primarily affects language skills, setting it apart from more common and well-known forms of …

- Early detection of primary progressive aphasia through speech and … — This condition can be detected early using a set of speech and hearing tests known as the Montreal-Toulouse Language Assessment Battery (MTL-BR).

- First Symptoms of Primary Progressive Aphasia and Alzheimer's … — Among the caregivers with PPA, 70% were female and had an average age of 52.4 (± 15) and an average education of 15.6 (± 1.5). 40% of the …

- Primary Progressive Aphasia — PPA is a condition caused by a neurological disease that gradually affects a person's ability to use and understand language.

Legal Disclaimers & Brand Notices

The content provided in this article is for informational and educational purposes only and does not constitute professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of a physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition, prognosis, or treatment plan. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read in this article.

All product names, logos, and brands mentioned herein are the property of their respective owners. All company, product, and service names used in this article are for identification purposes only. Use of these names, logos, and brands does not imply endorsement.