After a stroke or brain injury, aphasia changes how a person speaks, understands, reads, and writes. This article explains the key differences between Broca’s and Wernicke’s aphasia and offers practical, easy-to-do home activities caregivers and survivors can use to boost communication, memory, and connection. Clear, evidence-informed strategies aim to complement speech therapy and promote everyday success at home.

How Broca’s and Wernicke’s Aphasia Differ in brain location and symptoms

Understanding the neurological roots of aphasia helps make sense of the confusing changes in a loved one’s speech. Most aphasia cases stem from damage to the left hemisphere of the brain, which is the primary center for language in nearly all right-handed people and most left-handed individuals. Two specific areas play the biggest roles in how we process and produce words: Broca’s area and Wernicke’s area. While they work together in a healthy brain, damage to one or the other creates distinct communication challenges.

The Frontal Hub and Broca’s Aphasia

Neurological Basis

Broca’s aphasia occurs when there is damage to the left inferior frontal gyrus, often called Broca’s area. This part of the brain acts like a motor control center for language, helping us plan the movements needed to speak and organize words into grammatical sentences. Recent research into the neuroanatomy of Broca’s aphasia shows that the network is broad, involving deeper structures and nearby regions that coordinate complex speech tasks. When a large stroke affects the middle cerebral artery, it often damages this area along with the motor strip. Consequently, many people with Broca’s aphasia also have hemiparesis (weakness or paralysis on the right side of the body).

Classic Symptoms

The hallmark of this type is nonfluent speech. It feels like the words are stuck. A person might use telegraphic phrases, saying only the most important “content” words like nouns and verbs while omitting smaller words like “the,” “is,” or “and.” Auditory comprehension (the ability to understand what others say) is usually a strength, though it can be impaired for complex sentences. Repetition is almost always difficult. Many people also experience apraxia of speech, a struggle to coordinate the physical muscle movements to form sounds correctly.

The Temporal Hub and Wernicke’s Aphasia

Neurological Basis

Wernicke’s aphasia results from damage to the posterior superior temporal gyrus. This area is responsible for making sense of the sounds we hear and attaching meaning to words. Unlike Broca’s, this region is further back in the brain. It is less likely to cause physical paralysis because it is distant from the motor cortex. However, it is vital for the “dictionary” of the brain. Damage here breaks the link between a word and its meaning.

Classic Symptoms

This is known as fluent aphasia. Speech flows easily and sounds like a normal conversation in terms of speed and rhythm, but the content is often “empty.” The person may use paraphasias (substituting one word for another, like saying “chair” when they mean “table”) or neologisms (completely made-up words). According to clinical descriptions of Wernicke Aphasia, these patients often follow grammatical rules, but the sentences do not make sense. Auditory comprehension is severely impaired. Furthermore, they may not understand that they are making mistakes. This lack of awareness is called anosognosia. Repetition is also very difficult because they cannot process the input to mirror it back.

Comparing Reading, Writing, and Awareness

Writing usually parallels speech in both types. A person with Broca’s will likely write in short, effortful bursts with many spelling errors. A person with Wernicke’s might write pages of text that look like normal sentences but contain no clear meaning. Reading comprehension also differs. Those with Broca’s can often read for the main idea but struggle with grammar. Those with Wernicke’s may read aloud fluently but have no idea what the words actually mean.

Awareness is perhaps the biggest emotional difference. People with Broca’s are usually very aware of their struggles, leading to high levels of frustration. People with Wernicke’s may seem happy or unbothered initially because they truly believe they are communicating clearly. This can make home safety and following medical advice much harder for caregivers.

Recovery and Cognitive Deficits

Recovery patterns vary based on the size of the lesion. Broca’s aphasia often shows quicker initial gains in naming and sentence length. Wernicke’s recovery depends heavily on the person regaining awareness of their errors. Both types are often accompanied by other cognitive issues, including problems with attention (staying focused on a task), memory (holding onto new information), and executive function (planning and problem solving). These “hidden” deficits often impact daily life as much as the language loss itself.

Clinical Examples in Everyday Life

Example 1. Broca’s Aphasia

A husband is trying to tell his wife he wants a cup of coffee. He looks at the kitchen and says, “Coffee… black… please.” He looks frustrated and points to his mouth. When his wife asks if he wants sugar, he shakes his head and says, “No… just… coffee.” His speech is slow and requires great effort, but his meaning is clear.

Example 2. Wernicke’s Aphasia

A woman is talking to her daughter about her day. She says, “The flubber was gritting the purple sky on the desk for the morning.” She smiles and waits for a response as if she just said something perfectly normal. When her daughter looks confused, the woman repeats the sentence with the same confidence, unaware that the words are nonsensical.

Example 3. Mixed Transcortical Aphasia

A man sits quietly and rarely starts a conversation. When his caregiver says, “It is time for lunch,” he immediately repeats, “It is time for lunch.” However, he cannot answer the question, “What do you want to eat?” He has a strong ability to repeat what he hears, but he cannot generate his own thoughts or understand the meaning behind the words he is echoing.

How these differences shape everyday communication and care at home

How Communication Profiles Change Daily Life

Living with aphasia means every interaction requires a new strategy. In Broca’s aphasia, the frustration is often visible. You might see a loved one trying to tell you they are hungry; they know exactly what they want, but the words come out slowly. They might only say “Eat” or “Sandwich.” It feels like sending a text message with a very strict character limit. The effort is physical, and you can see the tension in their face as they try to force the sounds out.

Wernicke’s aphasia looks very different in a living room setting. The person might speak in long, flowing sentences with normal rhythm, but the words do not fit together. They might say “The paper is walking under the blue light” when they mean they are thirsty. Because they often do not realize they are making mistakes, they might get confused when you do not bring them a glass of water. This lack of awareness is a major hurdle for families; the person is not being difficult, but their brain is simply not registering the errors in their own speech.

Concrete Breakdowns in Common Situations

Consider the simple act of ordering food at a local diner. A person with Broca’s aphasia might prepare for twenty minutes, writing down “Burger, no onions.” When the server arrives, the pressure of the social situation makes the words even harder to find. They might struggle to hand over the paper or end up pointing at a picture on the menu, leaving the restaurant feeling exhausted from the mental workout.

Now imagine someone with Wernicke’s aphasia in that same diner. They might look at the server and say “I would like the green mountain with the fast shoes,” believing they ordered a salad. When the server asks for clarification, the person might repeat the same nonsense phrase with more emphasis, potentially becoming frustrated with the server for not understanding a “simple” request. This can lead to public scenes that are painful for caregivers to manage.

Safety at home is another area where these differences matter. Reading a medication label is a high-stakes task. A person with Broca’s aphasia can usually read the instructions and understand that “Take two pills at night” means exactly that; their challenge is telling you they took them. A person with Wernicke’s aphasia might look at the same label and see only shapes, or read the words aloud without the meaning reaching the brain. They might take the wrong dose because they cannot process the written warning. This is why Wernicke Aphasia – StatPearls emphasizes the depth of comprehension deficits.

Impact on Activities of Daily Living

Phone calls are often the first thing people with aphasia stop doing. For someone with Broca’s aphasia, the lack of visual cues is terrifying because they cannot use hand gestures to help you understand. Appointments become a team effort where caregivers must often act as interpreters. During a doctor visit, a patient with Broca’s aphasia might nod along but struggle to describe their pain, needing extra time to answer.

Social visits change the family dynamic. In Broca’s aphasia, the person often becomes a listener, staying in the room but stopping their contribution, which leads to profound social withdrawal. In Wernicke’s aphasia, the person might dominate the conversation, talking over others because they do not pick up on social cues. They might not notice when a guest looks confused or uncomfortable, which can alienate friends who do not understand the condition.

Emotional and Behavioral Realities

Caregivers should prepare for intense emotional shifts. Frustration is the hallmark of Broca’s aphasia. Imagine being trapped in a room where you can hear everyone but you can only speak through a tiny straw. This leads to outbursts or deep bouts of depression. Fatigue is also a major factor; speaking a single sentence can feel like running a marathon.

In Wernicke’s aphasia, you might see paranoia or agitation. If the person thinks they are speaking clearly and you keep saying “I don’t understand,” they might think you are playing a trick on them or ignoring them. This is a result of the brain injury, not a change in their personality. Understanding the Aphasia – ASHA guidelines helps families realize that these behaviors are symptoms of the language breakdown.

Screening for Associated Problems at Home

Families can play a huge role in spotting other issues that change how we provide care. Watch for these signs:

- Apraxia of Speech

The person knows the word but their mouth looks like it is fumbling. They might make several attempts to get the first sound out. This is a motor planning issue. - Dysarthria

The speech sounds slurred or muffled. This is caused by actual weakness in the muscles of the face or tongue. - Hemiparesis

Weakness on one side of the body is common. It usually affects the right side in Broca’s aphasia (left brain injury). This makes using a phone or writing even harder. - Visual Field Cuts (Hemianopsia)

The person might not see things on the right side of their vision. They might bump into doorframes or only eat food from the left side of their plate because the right visual field is missing. - Memory Impairments

They might forget what you said two minutes ago. This is separate from the language issue but makes following directions much harder.

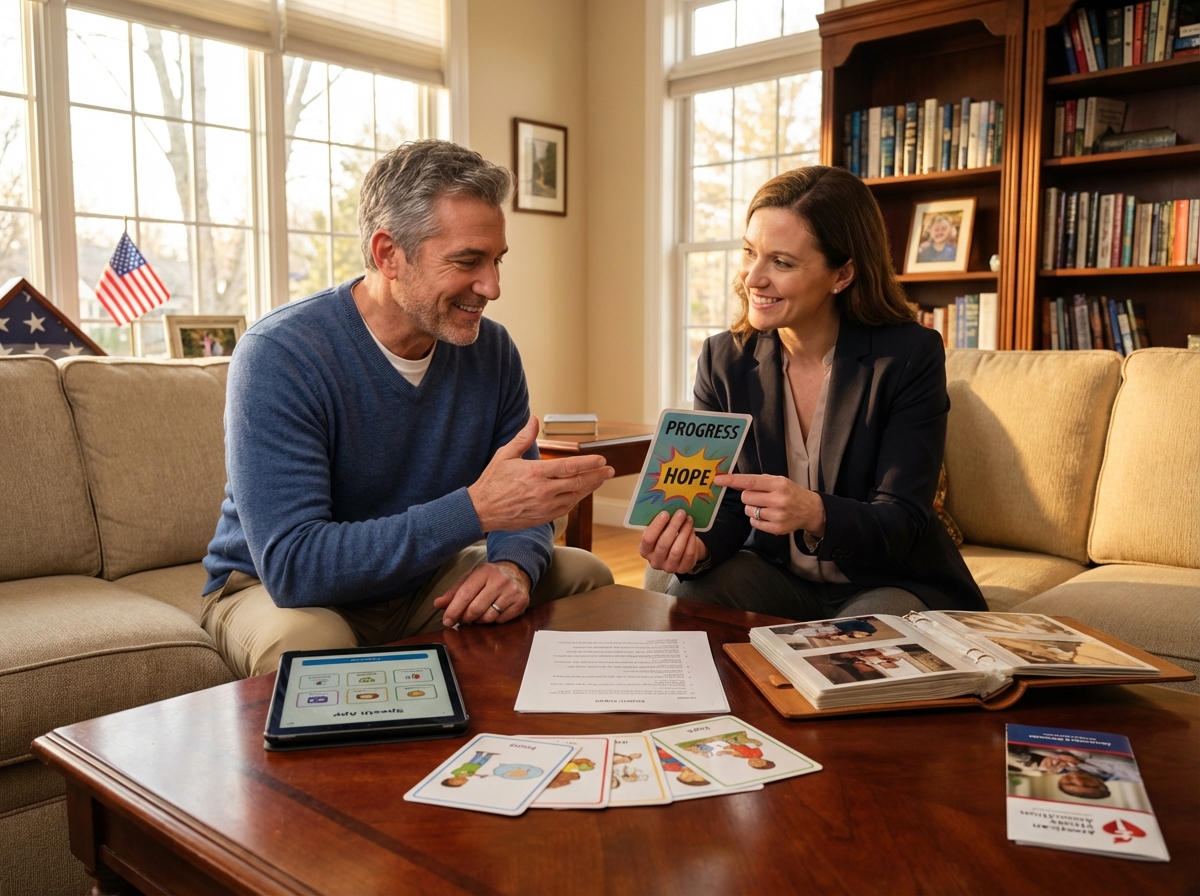

Setting Realistic Goals with a Professional

Working with a Speech-Language Pathologist (SLP) is essential. You need goals that are measurable and functional. Do not aim for “perfect speech.” Instead, aim for “ordering a coffee using a three-word phrase.” This is a goal you can track. For someone with Wernicke’s aphasia, a goal might be “following a two-step command like ‘pick up the pen and put it on the table’ with 80 percent accuracy.”

Small gains are the key to long-term recovery. You might notice that they are using more gestures or are less frustrated during dinner. These are huge wins. Recent research into The neuroanatomy of Broca’s aphasia – Frontiers shows that the brain can find new ways to process language. Tracking these small steps helps the family stay motivated when the road feels long. Focus on connection rather than perfection.

Practical home activities tailored for Broca’s and Wernicke’s aphasia

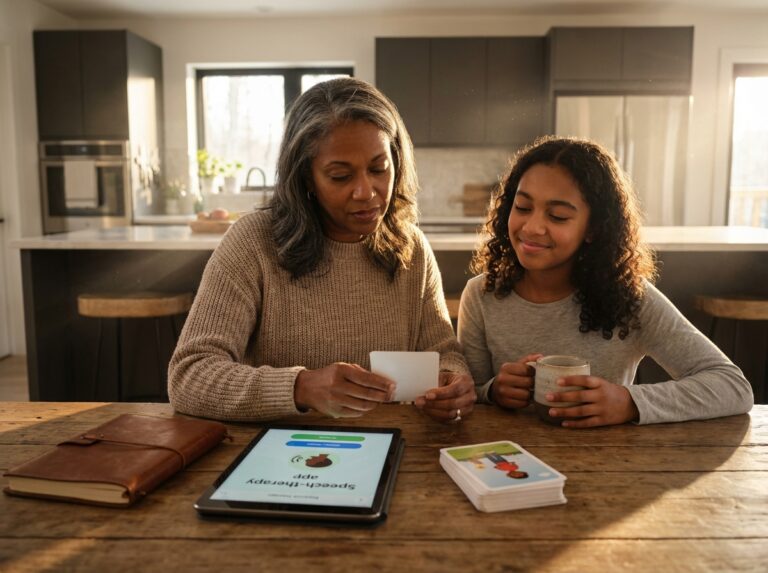

Building a recovery routine at home requires a shift in how we think about practice. It is not just about doing drills; it is about creating a space where communication feels safe. For those dealing with Broca’s aphasia, the focus remains on the physical act of producing speech. For Wernicke’s aphasia, the priority is helping the brain make sense of the sounds it hears. These activities work best when they are part of a daily rhythm rather than a stressful chore.

Home Activities for Broca’s Aphasia

Script Training

The purpose of script training is to automate common phrases so they become effortless. Choose a sentence that the person needs every day, such as “I would like a glass of water.” Start by saying the sentence together in unison. Next, move your lips while the person says it aloud. Finally, the person tries to say it alone. Practice one script for 15 minutes twice a day. To make this easier, use only two words like “Want water.” To make it harder, add a second part such as “I would like water with ice.”

Melodic Intonation Adapted for Home

This technique uses the musical side of the brain to jumpstart the language side. Pick a functional phrase and sing it using only two notes. Hold the person’s hand and tap out the rhythm of the syllables on a table. The rhythm helps the brain find the timing for the words. Try this with “Good morning” or “Time to eat.” Practice this for 10 minutes during morning routines. If the person struggles, slow the tempo down significantly.

Repetition Drills with Cueing Hierarchies

This activity helps the person find words when they feel stuck. Show an object like a spoon. If they cannot name it, give a hint about what it does (“You use this to eat soup”). If they still cannot say it, give them the first sound (“It starts with an S”). The goal is to provide just enough help so they can say the word themselves. Do this with five household items every afternoon to build confidence in word retrieval.

Writing to Speak Pairing

Many people with Broca’s aphasia find that writing the first letter of a word helps them say it. Keep a small whiteboard nearby. When the person wants to say “Coffee,” have them write the letter C first. This physical act often triggers the verbal response. Use this during meal times to practice naming foods.

Home Activities for Wernicke’s Aphasia

Comprehension First Strategies

The main challenge here is the “word salad” where speech is fluent but lacks meaning. Focus on listening before speaking. Use very short sentences and ask questions that only require a yes or no answer. You can also use forced-choice questions. Instead of asking “What do you want to drink,” hold up milk and juice and ask “Do you want milk or juice.” This provides a visual cue that anchors the language.

Structured Reading for Comprehension

Reading can help ground the person when spoken words feel confusing. Print out a very short paragraph about a familiar topic like gardening or weather. Ask the person to read it, then ask one simple question about the text. For example, if the text says “The sun is hot,” ask “Is the sun cold.” This forces the brain to process the meaning of the symbols. You can find more structured approaches in the Treatment of Wernicke’s Aphasia guide. Start with one sentence and move to three sentences as they improve.

Errorless Learning for Naming

In Wernicke’s aphasia, the person might say the wrong word and not realize it. Errorless learning prevents the brain from practicing mistakes. Instead of asking “What is this,” say “This is a phone. Say phone.” This ensures they only hear and say the correct word. Use this for 10 minutes a day with family photos to reduce the frustration of circular conversations.

Shared Strategies and Technology

Spaced Retrieval for Memory

This helps the person remember important information like a phone number or a caregiver’s name. Ask a question and have them give the answer. Wait 30 seconds and ask again. If they get it right, wait one minute, then two minutes. This builds long-term retention and is very effective for safety information. Do this once an hour for a few hours until the information sticks.

PACE Style Conversation Scaffolds

PACE stands for Promoting Aphasics’ Communicative Effectiveness. It treats conversation like a game where you and the person take turns describing a hidden picture using drawing, gestures, or pointing. The goal is to get the message across by any means necessary, reducing the pressure to be grammatically correct and encouraging the use of low-tech AAC templates like picture boards.

Technology and US Resources

Many families find success with tablet apps like Tactus Therapy or Lingraphica, which allow for high repetition practice without a therapist present. For those with severe expression issues, a dedicated speech-generating device might be necessary. Consult with an expert through ASHA to find a certified professional. Organizations like the National Aphasia Association and the American Stroke Association offer directories for local support groups in the USA, providing a vital social setting for practice.

Safety and Practice Tips

Practice should never last more than 30 minutes at a time. Fatigue is the enemy of progress. If you see the person rubbing their eyes or becoming irritable, stop immediately. Use positive reinforcement for every effort; even a wrong word is a sign that the brain is trying. Keep a simple log of what activities you did and how they went to see small gains over weeks that might be hard to notice day to day.

Ready to Use Exercises

One Sentence Script for Food

I would like to eat dinner now.

Two Step Command Practice

1. Pick up the blue pen. 2. Put the pen on the paper.

Naming Drill Script

Caregiver: (Points to a key) This is a key. What is it? Survivor: Key. Caregiver: Good. We use the key to open the... Survivor: Door.

Family Photo Description Task

Look at this photo of your grandson. What color is his shirt? Is he smiling or crying?

Short Comprehension Check

Read this: The apple is red. It is on the table. Question: Is the apple on the floor? (Yes/No)

Common questions people ask about aphasia and home practice

Families often feel overwhelmed by the technical terms used in hospitals. Understanding the practical side of recovery helps reduce that stress. Here are the answers to the questions that come up most often during home practice sessions.

What is the main difference between Broca’s and Wernicke’s aphasia in simple terms?

Broca’s aphasia is “non-fluent”: the person knows what they want to say but cannot get the words out. Wernicke’s aphasia is “fluent”: the person speaks easily with a natural rhythm, but the words are often wrong or made up, and they may not understand others. StatPearls provides a clinical overview of these distinctions.

Tip. For Broca’s, give them extra time to finish sentences. For Wernicke’s, use gestures to help them understand your meaning.

Can aphasia get better on its own and when should we see an SLP?

The brain goes through a period of spontaneous recovery in the first few months after an injury as swelling goes down. However, working with a Speech-Language Pathologist (SLP) is necessary to maximize this window. You should see an SLP as soon as the person is medically stable.

Tip. Start professional therapy early to take advantage of the brain’s natural healing phase.

How often should we practice at home and what is a realistic daily routine?

Consistency is more important than long hours. Aim for 15 to 30 minutes of focused practice twice a day to prevent fatigue. A routine might include a morning session for naming objects and an afternoon session for reading or listening tasks.

Tip. Use a kitchen timer to keep sessions short and manageable for both of you.

When should we introduce AAC or an app and what type suits each aphasia type?

Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) can be introduced at any stage. For Broca’s aphasia, high-tech apps with buttons for common phrases work well. For Wernicke’s aphasia, low-tech visual boards with pictures are often better because they help the person focus on meaning rather than complex navigation.

Tip. Start with a simple paper picture board before buying expensive software.

How do I reduce frustration and help my loved one stay motivated?

Acknowledge the difficulty by saying things like “I know this is hard.” Focus on what they can do rather than what they cannot. Use activities that involve their hobbies, such as looking at family photos or listening to favorite music.

Tip. End every practice session with a “win” by doing an activity you know they can complete successfully.

Is it safe to drive or manage medications with aphasia?

Aphasia affects language, but it can also impact the ability to read labels or understand road signs. Safety is the priority. You should ask for a formal driving evaluation from an Occupational Therapist. For medications, use a pill organizer and a visual chart with photos of the pills.

Tip. Consult your doctor for a referral to a driving rehabilitation specialist to assess the actual risk.

What if the person seems unaware of their language problems?

This is common in Wernicke’s aphasia (anosognosia). The person may get angry when you do not understand them because they think they are speaking clearly. Do not argue with them. Instead, use gentle verification strategies like “I think you are talking about lunch, is that right?”

Tip. Use a “thumbs up” or “thumbs down” system to check for understanding without causing a confrontation.

How do I find an SLP, support groups, or financial help in the USA?

The ASHA website has a “ProFind” tool to locate certified therapists in your area. For support groups, the National Aphasia Association maintains a database of local chapters. Financial help may be available through state vocational rehabilitation programs or non-profit grants.

Tip. Search for “Aphasia Community Groups” in your city to find peer support for caregivers.

What are the insurance and Medicare basics for speech therapy access?

Medicare Part B typically covers 80 percent of the cost for medically necessary speech therapy after you meet your deductible. There is no longer a hard “cap” on therapy, but your SLP must use a specific code to show the treatment is still helping. Private insurance varies, so always check your “Summary of Benefits” for outpatient therapy limits.

Tip. Ask your SLP to provide a written progress report every 30 days to help with insurance approvals.

How do we make teletherapy work at home?

Teletherapy is a great option if you cannot travel. You need a quiet room with good lighting so the therapist can see the person’s mouth. A tablet or laptop is better than a phone because the screen is larger. Make sure the person is wearing their glasses or hearing aids before the session starts.

Tip. Do a “tech check” five minutes before the appointment to ensure the microphone and camera are working.

What factors affect the long term prognosis?

Prognosis depends on many things including the size of the brain injury, the person’s age, and their overall health. Recent research suggests that the network of brain regions involved is very complex. Some people see major improvements in the first year, while others make slow progress over many years.

Tip. Focus on functional goals, like being able to order coffee, rather than “perfect” speech.

What if we hit a plateau in progress?

Plateaus are a normal part of the recovery process. It does not mean the person will never improve again; it often means the brain needs a break or a change in the type of practice. You might try a different approach, such as Tactus Therapy methods for Wernicke’s, or take a week off to focus on social activities.

Tip. Discuss a “maintenance plan” with your SLP to keep skills sharp during these slower periods.

Takeaways and next steps for families and caregivers

Transitioning from understanding the diagnosis to building a functional home routine requires patience and strategy. Since recovery is a marathon, it requires consistent daily engagement rather than occasional intense bursts. Recent studies on the neuroanatomy of Broca’s aphasia show that the damage often extends beyond a single point in the brain, meaning recovery is complex and ongoing.

A Thirty Day Starter Plan for Families

The first month of home practice should focus on establishing a rhythm without causing exhaustion. You can follow this structured approach to build momentum.

Week One. Baseline and Professional Connection

Your primary goal is to observe and document. Spend fifteen minutes twice a day recording which communication attempts succeed. Contact a speech-language pathologist to schedule an evaluation if you have not done so. You can find certified professionals through the ASHA website. Use this week to identify the times of day when your loved one has the most energy for practice.

Week Two. Caregiver Communication Training

Shift the focus to how you speak. For Broca’s aphasia, practice the “wait ten seconds” rule before offering a word. For Wernicke’s aphasia, practice using short sentences with one idea at a time. Research on the treatment of Wernicke’s aphasia suggests that reducing background noise is essential for improving comprehension. Start a daily ten-minute session of “supported conversation” where the goal is connection rather than perfect grammar.

Week Three. Integrating Tools and Apps

Introduce one digital tool or a physical communication board. If the person has Broca’s aphasia, look for naming exercises. If they have Wernicke’s aphasia, look for auditory processing tasks. Limit app use to twenty minutes a day to prevent frustration. Ensure the exercises match the specific type of language deficit identified by your therapist.

Week Four. Goal Review and Social Expansion

Evaluate the progress made over the last twenty-one days. Set one social goal for the upcoming month, such as a short visit from a friend or a trip to a quiet park. Continue the thirty minutes of daily practice but vary the activities to keep them engaging. Contact your therapist to discuss the next steps based on your observations.

Establishing Measurable Goals with an SLP

Working with a professional allows you to set SMART goals (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, Time-bound). Instead of a vague goal like “talking better,” you should aim for “naming five common kitchen items independently.” Your speech-language pathologist will help you determine when it is time to consider advanced options, such as intensive aphasia programs or augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) devices. These tools can provide a voice for those with severe expressive limitations. Outpatient clinics often provide specialized equipment that is not available for home use, and you should ask about group therapy options which provide social stimulation alongside language practice.

Emotional Support and Meaningful Connection

Living with aphasia is frustrating for the survivor and equally difficult for the caregiver. It is important to validate these feelings; you are allowed to feel tired and sad about the change in your communication. You can build a deep connection that does not rely on spoken language. Music is a powerful tool for this, as many people with aphasia can sing even when they cannot speak. Listen to favorite albums together or look through old photographs to spark memories. Physical touch is another vital form of communication; a hand on the shoulder or a hug can provide comfort when words fail. Peer support is a critical resource for long-term resilience. Organizations like the National Aphasia Association offer virtual support groups, allowing you to share tips with others navigating the same challenges in the USA.

Trusted Resources and Search Terms

Finding the right help requires knowing where to look. You can use these organizations for reliable information.

- ASHA. The American Speech-Language-Hearing Association provides a directory of licensed therapists.

- National Aphasia Association. This group offers educational materials and a list of local support chapters.

- American Stroke Association. They offer resources for stroke recovery and tips for caregivers.

When searching online for local help, use specific terms like “aphasia center near me” or “neurogenic communication disorders clinic.” You can also search for “university speech and hearing clinic” as these often provide services at a lower cost. If you need immediate emotional support, you can call the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline in the USA. They are equipped to handle the emotional distress that often accompanies chronic illness or disability.

| Aphasia Type | Primary Home Goal | Key Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Broca’s | Word Retrieval | Provide extra time. Use sentence starters. |

| Wernicke’s | Comprehension | Use visual aids. Minimize background noise. |

| Global | Basic Needs | Use picture boards. Focus on gestures. |

Progress in aphasia recovery is rarely a straight line. There will be days when communication feels impossible and days when a new word emerges clearly. Focus on the small victories. Every successful exchange is a step toward a more connected life. Keep your practice sessions short, your goals realistic, and remember that your presence and patience are the most valuable tools in this journey.

Sources

- The neuroanatomy of Broca's aphasia – Frontiers — Recent evidence suggests that the neuroanatomy of Broca's aphasia is far more complex, implicating a broader network of cortical and subcortical regions.

- Aphasia – StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf – NIH — Clinically, common types of aphasia include Broca and Wernicke aphasia … Network-based statistics distinguish anomic and Broca aphasia. ArXiv …

- Aphasia: Types, Causes, Prevalence, and Treatment Options — Broca's aphasia can occur due to damage to the brain's frontal lobe. … Also known as fluent aphasia, people having Wernicke's aphasia can …

- Wernicke Aphasia – StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf – NIH — Unlike Broca aphasia, patients with WA speak with normal fluency and prosody and follow grammatical rules with normal sentence structure.

- Treatment of Wernicke's Aphasia (TWA) Guide for Speech Therapy — Six of the nine subjects had Wernicke's aphasia. After more than 20 hours of therapy in 2 weeks, 2/3rds of the subjects improved significantly on measures of …

- Aphasia – ASHA — Aphasia is an acquired neurogenic language disorder resulting from brain injury. Aphasia may affect receptive and expressive language.

- The Fast Facts on Aphasia – Universal Health Fellowship — Broca's Aphasia is associated with right-sided paralysis and weakness. Comprehensive (Wernicke's) Aphasia. Those with Wernicke's Aphasia tend …

- Comparison of Large Language Model with Aphasia – Watanabe — In particular, for Wernicke's aphasia, we also have to clarify behavioral and linguistic differences between its symptoms and typical …

- [PDF] Broca's vs. Wernicke's aphasia – Iowa Research Online — As previously discussed, compared to people with Wernicke's aphasia, those with Broca's aphasia tend to produce more sparse and effortful verbal output, while …

Legal Disclaimers & Brand Notices

The content provided in this article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition, stroke recovery, or speech-language pathology. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read in this article.

All product names, logos, and brands mentioned in this text are the property of their respective owners. All company, product, and service names used in this article are for identification purposes only. Use of these names, trademarks, and brands does not imply endorsement.