Anomic aphasia commonly leaves people frustrated by tip-of-the-tongue moments — the inability to find a familiar word despite knowing its meaning. This article explains the brain mechanisms behind word-finding breakdowns after stroke or injury and offers practical, evidence-based home practice strategies for improving retrieval, supporting memory, and keeping communication active for people living with aphasia and their caregivers.

Understanding Anomic Aphasia and Tip of the Tongue

We’ve all had that frustrating moment. You’re in the middle of a sentence, and a common word suddenly vanishes. It’s right there, on the very edge of your thoughts, but you just can’t grasp it. This is the “tip-of-the-tongue” feeling, and for someone with anomic aphasia, it’s not just an occasional annoyance. It can be a constant, exhausting barrier to communication that happens dozens of times a day. Anomic aphasia is the most common type of aphasia, a language disorder that affects about 2 million people in the U.S. and often occurs after a stroke or brain injury. It is estimated that 20% to 40% of individuals diagnosed with stroke have aphasia. This condition specifically impacts your ability to retrieve words, especially the names of people, places, and objects.

Imagine this. John is telling his wife, Sarah, about his physical therapy session. “It was good,” he says, gesturing with his hands. “We used the… you know… the big machine. The one you walk on. It goes fast or slow.” He snaps his fingers, his face tight with frustration. He knows exactly what he wants to say. He can picture it, describe its function, and even feel the rhythm of walking on it. He might even know it starts with a ‘t’ sound. But the word “treadmill” is stuck behind a locked door. Sarah, trying to help, might guess, “The bike?” John shakes his head, the frustration mounting. This isn’t like when Sarah forgot the name of an actor last night; that word came back to her an hour later while she was washing dishes. For John, this word-finding block is persistent and deeply affects his ability to share his experiences. This is the daily reality of anomic aphasia.

So, what is happening in the brain to cause this? Word retrieval is a complex, multi-step process that happens in fractions of a second. Think of your vocabulary as a massive, intricate library. To say a word, your brain must:

- Access the meaning (Semantic Access). You first need to have the concept or idea you want to express. This is like knowing which book you want from the library.

- Find the word itself (Lexical Selection). Your brain then has to locate the specific word form that matches that meaning from among thousands of options. This is like finding the correct book on the shelf.

- Get the sounds ready (Phonological Encoding). Finally, your brain has to retrieve the sound map for that word so your mouth can produce it correctly. This is like being able to read the title of the book aloud.

Anomic aphasia occurs when there is a breakdown at one or more of these stages. The damage is most often caused by an event that disrupts blood flow or causes direct injury to the language centers of the brain, which are typically in the left hemisphere. Common causes include an ischemic stroke (a blockage), a hemorrhagic stroke (a bleed), a traumatic brain injury (TBI), or a brain tumor. It can also be a symptom of a neurodegenerative condition like Primary Progressive Aphasia (PPA).

The specific location of the brain injury often determines the nature of the word-finding difficulty. Damage to the left posterior temporal lobe or the angular gyrus can disrupt the connection between a word’s meaning and its name, like having a faulty library catalog. An injury to inferior frontal areas, like Broca’s area, might interfere more with retrieving the sound pattern of the word, even if the meaning and word form are accessible. It’s not just about one spot, though. Modern neuroscience shows us that language relies on a widespread network. An injury can damage a key “hub” or simply disrupt the “pathways” connecting different language areas, causing communication breakdowns.

While everyone experiences tip-of-the-tongue moments, the word-finding failures in anomic aphasia are different in several key ways.

- Frequency. For a person with anomic aphasia, these blocks happen constantly throughout the day, not just once in a while with an obscure word.

- Impact. It significantly disrupts the flow of conversation, causing immense frustration and sometimes leading to social withdrawal. The person often uses vague words like “thing” or “stuff” or talks around the missing word (a strategy called circumlocution).

- Co-occurring Issues. Word-finding difficulty is often not the only challenge. A person might also have mild comprehension issues, trouble with working memory (holding information in mind), or apraxia of speech, which is a motor planning problem that makes it hard to coordinate the muscle movements for speech.

A speech-language pathologist (SLP) diagnoses anomic aphasia through a comprehensive evaluation. This usually involves naming tests (like showing pictures of objects), analyzing a sample of connected speech from a conversation, and checking single-word comprehension to ensure the person still understands the words they can’t retrieve.

Recovery is a journey, and several factors influence the prognosis, including the size and location of the brain injury, the person’s age and overall health, and, crucially, their motivation and access to therapy. This is where home practice becomes so powerful. The brain is not static; it has an incredible ability to reorganize itself, a process called neuroplasticity. When you consistently and repetitively practice retrieving words, you are actively encouraging your brain to strengthen existing neural pathways or create new ones. Each successful attempt to name a picture, complete a phrase, or use a target word in conversation is like paving a new road in that mental library, making the path to that word stronger and faster for the next time. Targeted home practice isn’t just busywork; it’s a biologically plausible way to drive recovery and rebuild the connections that make communication possible. The strategies that follow are designed to help you do just that.

Home Practice Strategies to Improve Word Finding

After understanding the “why” behind word-finding difficulties, the next step is taking action. Consistent, targeted home practice can strengthen the neural pathways for language and build confidence. Think of these strategies not as tests, but as supportive workouts for the brain. The goal is successful communication, not perfect performance. Below are practical, evidence-based activities you can adapt for home use.

Semantic Feature Analysis (SFA)

SFA is a powerful technique that helps rebuild the brain’s “filing system” for words by focusing on their meaning and features. Instead of just trying to recall the word itself, you describe it from multiple angles.

How to do it:

Choose a target word, perhaps using a picture card or a real object. Let’s use a banana. Ask a series of questions to describe its features.

- Category: What group does it belong to? (It’s a fruit.)

- Use: What do you do with it? (You peel it and eat it.)

- Action: What does it do? (It grows on a tree.)

- Properties: What does it look, feel, or taste like? (It’s yellow, soft, sweet.)

- Location: Where would you find it? (In a grocery store, in a lunchbox.)

- Association: What does it make you think of? (Monkeys, smoothies.)

Often, by the time you go through these features, the word “banana” will pop out. If it doesn’t, the caregiver can provide the word. The main work is strengthening the connections around the word.

Variations: For more severe aphasia, start with just two or three features, like category and use. For milder aphasia, add more complex features like “What are its parts?” (peel, stem).

Frequency: Aim for 10-15 minute sessions, 3-4 times per week, focusing on 5-10 words per session.

Troubleshooting: If the person is struggling to answer a feature question, offer a choice. For example, “Is it a fruit or a vegetable?”

Phonological and Phonemic Cueing

This strategy focuses on the sounds within a word. It’s especially helpful when the person knows what they want to say but can’t access the sounds to produce it.

How to do it:

Use a hierarchy of cues, starting with the least helpful and moving to the most helpful. This gives the brain a chance to retrieve the word at each level.

- Level 1 (Sentence Completion): “You drink coffee out of a…”

- Level 2 (Rhyming): “It rhymes with ‘hug’…”

- Level 3 (First Sound): “It starts with the sound /m/…”

- Level 4 (First Syllable): “It starts with ‘muh’…”

- Level 5 (Provide the Word): “The word is mug. Can you say mug?”

Frequency: Integrate this into daily conversation or during naming practice for 5-10 minutes daily.

Troubleshooting: Be careful not to provide cues too quickly. Give at least 5-10 seconds of quiet thinking time before offering the first cue. Over-cueing can create dependence.

Spaced Retrieval Training

This technique uses the brain’s ability to learn and retain information by practicing recall over progressively longer intervals. It’s excellent for learning important names, facts, or strategies.

How to do it:

- State a fact or show a picture with its name. For example, “This is your grandson, Mark.”

- Immediately ask, “What is his name?”

- If correct, wait 15 seconds and ask again.

- If correct again, double the interval to 30 seconds, then 1 minute, 2 minutes, 5 minutes, and so on.

- If an incorrect answer is given at any interval, provide the correct answer immediately (“His name is Mark”) and go back to the last interval where they were successful.

Frequency: Practice 1-3 important pieces of information for 10 minutes, 3-5 times per week.

Script Training

Script training helps automate common conversational phrases, reducing the cognitive load of word finding in routine situations.

How to do it:

- Choose a personally relevant routine, like ordering a coffee or greeting a neighbor.

- Write a short, simple script. For example, “Hi. I’d like a large black coffee, please.”

- Practice the script line by line, using repetition and choral reading (saying it together).

- Use a voice recorder to listen back and practice independently.

Sample 2-Week Plan:

- Week 1: Practice each line of the script 10 times daily. Use phonemic cues for difficult words.

- Week 2: Practice the whole script in a role-playing scenario. Try to say it from memory, with the written script available as a backup.

Integrating Other Helpful Principles

Errorless Learning:

Use this when introducing new, difficult words or when frustration is high. Instead of letting the person guess incorrectly, provide the answer immediately and have them repeat it. This builds a correct memory trace from the start.

Multimodal Cueing:

Encourage using any and all means of communication. If a word is stuck, ask, “Can you show me with your hands?” or “Can you draw it?” Using gestures, writing the first letter, or pointing to a picture are all valid and helpful ways to communicate and can sometimes trigger the spoken word.

Adapted Constraint-Induced Practice:

At home, this can be a simple, high-intensity game. Set a timer for 5 minutes. Go through a stack of 10 picture cards, encouraging the person to say the name of each. The “constraint” is to gently encourage verbal production over just pointing. Do this 2-3 times a day for a quick, focused burst of practice.

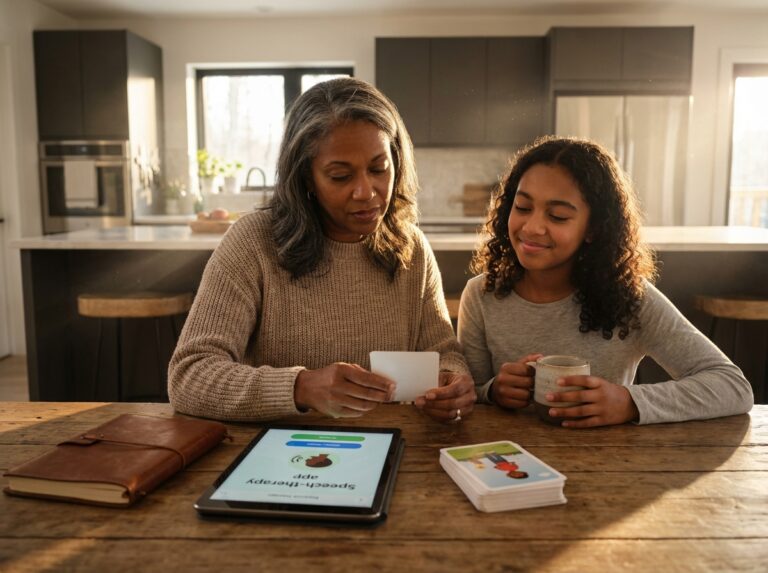

Tools for Home Practice

You don’t need expensive equipment. Many effective tools are already in your home.

Low-Tech Tools:

- Picture Cards: Use flashcards (store-bought or homemade from magazines) of common objects.

- Photo Albums: Practice naming family members, friends, and places from personal photos.

- Labeled Household Items: Place sticky notes with names on items around the house (e.g., “refrigerator,” “microwave”).

High-Tech Tools:

- Tablets/Smartphones: Look for aphasia-friendly apps that allow you to customize naming practice with your own pictures and words. Many include built-in progress reports that track accuracy and response time.

- Voice Recorders: Useful for script training and for recording yourself saying target words to play back for practice.

- Teletherapy: This provides direct access to an expert SLP from the comfort of your home, eliminating travel and making it easier to involve the whole family in sessions. It works best when integrated into a plan that also includes real-world conversation practice.

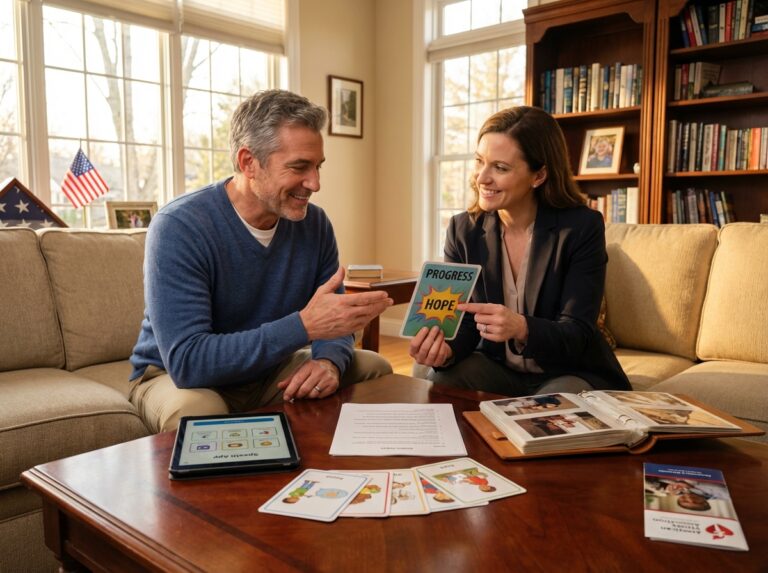

Caregiver Communication Strategies

How you support your loved one is just as important as the exercises you do. Your role is to be a supportive partner, not a tester. Family members can be fantastic practice partners, especially when following a plan created with an SLP. The goal is successful communication and confidence-building.

- Create a relaxed environment. Avoid pressure. Say things like, “Take your time, there’s no rush.”

- Ask, don’t test. Instead of “What is this?” try incorporating the word into a natural question, like “Do you want to use the fork or the spoon?”

- Offer choices. If they are stuck on a word, offer a choice: “Were you thinking of the dog or the cat?”

- Use yes/no questions. Simplify complex questions to a yes/no format to confirm their meaning.

- Acknowledge the struggle. Validate their frustration by saying, “I know it’s right there on the tip of your tongue. That’s so frustrating. Let’s describe it together.”

- Agree on a signal. Before you start a practice session, agree on a signal for when frustration is building. It could be a simple hand gesture or a phrase like “Let’s pause.” This empowers the person with aphasia to control the session’s pace.

Sample Weekly Schedule and Tracking

Consistency is key. A little practice each day is more effective than one long session per week. To make practice an automatic part of your routine, try linking it to an existing daily habit, such as doing your exercises for 15 minutes right after breakfast.

Sample Schedule:

- Monday: 15 min SFA with kitchen objects.

- Tuesday: 10 min script practice for morning routine.

- Wednesday: 15 min spaced retrieval for 2 important phone numbers.

- Thursday: 10 min phonological cueing game with magazine pictures.

- Friday: 15 min SFA with new words.

- Saturday: 10 min script practice role-play.

Simple Tracking Log:

Keeping a simple log can help you see progress and identify which cues are most helpful. You might also keep a “Success Journal” to write down one communication moment that went well each day, no matter how small. This helps measure progress beyond just correct words, focusing on increased confidence and reduced frustration.

| Date | Word/Script | Cues Used | Success? (Yes/No/With Help) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12/27/2025 | “Spoon” | SFA (Use) | Yes |

| 12/28/2025 | “Good morning” | Repetition | With Help |

Managing Frustration and Fatigue

Recovery is not linear. There will be good days and bad days. Fatigue, stress, and cognitive load can all make word finding harder. It’s vital to be kind to yourself and your loved one.

- Keep sessions short. Stop before frustration sets in. 10-15 minutes is often plenty.

- Know when to stop. If you see signs of distress like crying, anger, or shutdown, it’s time to take a break. Switch to a non-demanding, enjoyable activity.

- Celebrate all communication. A gesture, a drawing, or a successfully typed word is a win.

- Prepare for social situations. For challenging social settings, preparation is key. Have a simple, pre-planned way to explain the situation, such as a small, laminated card you carry or a practiced phrase. It is also okay to exit a conversation that has become too overwhelming.

- Seek professional help. It’s always best to start with a professional evaluation from an SLP. Consider restarting therapy if you feel progress has stalled for several weeks, if communication becomes significantly more difficult, or if you simply want to learn new strategies to advance your home practice. Think of an SLP as a coach you can check in with periodically to refine your game plan.

Conclusions and Next Steps

Navigating the path forward after a diagnosis of anomic aphasia can feel overwhelming, but it is a journey of rediscovery, not a final destination. Throughout this article, we’ve explored the frustrating “tip-of-the-tongue” moments that define this condition, understanding them not as a failure of intellect but as a disruption in the brain’s complex word-finding system. The most important takeaway is that you have the power to actively participate in rebuilding these connections. Progress is not only possible; it is achievable through consistent, targeted practice that leverages the brain’s incredible capacity for change, known as neuroplasticity.

The strategies discussed—from Semantic Feature Analysis to Script Training—are not random drills. They are designed to create new neural detours or strengthen weakened connections, making the pathway to a word clearer and more reliable. When you engage in these activities, you are quite literally helping your brain rewire itself. This knowledge transforms practice from a chore into an act of empowerment, giving purpose to every effort you make.

This journey is not meant to be taken alone. The involvement of a communication partner—a spouse, family member, or friend—is invaluable. A supportive partner who understands the strategies and can create a patient, positive environment for practice can dramatically accelerate progress. Equally important is the guidance of a certified Speech-Language Pathologist (SLP). An SLP can provide a formal assessment, create a personalized therapy plan tailored to specific needs and goals, and adjust the plan as skills improve. Home practice is most effective when it complements and reinforces the work being done in professional therapy sessions. You can find qualified professionals through resources like the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA).

To help you begin, here is a simple, actionable checklist to turn these ideas into a concrete plan.

- Schedule an SLP Evaluation. If you haven’t already, get a professional assessment to establish a baseline and create a tailored therapy plan. This is the most critical first step.

- Choose Three Targets. Don’t try to fix everything at once. Select three personally meaningful words or three short, useful scripts to focus on for the next two weeks.

- Set a Daily Practice Time. Consistency is key. Block out just 15 minutes each day dedicated to focused practice using the strategies discussed.

- Track Your Progress. Use a simple notebook to jot down the date, the words you practiced, and how you did (e.g., number of correct retrievals, level of cueing needed). This helps you see your improvement over time.

- Find Your Community. Reach out to a local or online aphasia support group. Connecting with others who understand the experience provides emotional support and practical advice. Teletherapy is also an excellent option for accessible, professional guidance from home.

Recovery from aphasia is a marathon, not a sprint. There will be good days and challenging days, but every small effort contributes to the larger goal. By embracing consistent practice, leaning on your support system, and celebrating every step forward, you can rebuild your communication skills and forge a confident path ahead.

Sources

- Aphasia Statistics – WordsRated — In the US, Aphasia affects around 2 million people. · 1 in 272 Americans are affected with Aphasia and there are 180,000 new cases in the US …

- Aphasia – StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf – NIH — … aphasia in the United States each year, affecting 1 in every 272 Americans. … Network-based statistics distinguish anomic and Broca aphasia.

- Aphasia – ASHA — Using these data, Simmons-Mackie (2018) estimates the prevalence rate of tumor-associated aphasia to be between 198,028 and 330,048. Signs and Symptoms.

- Aphasia: Types, Causes, Prevalence, and Treatment Options — Anomic aphasia: This is the least severe form of aphasia where … About 1 million people in the U.S are currently suffering from aphasia.

- About Aphasia — Approximately every four minutes in the United States someone acquires aphasia, a devastating language disorder dramatically impacting conversational …

- Aphasia – MEpedia — Approximately 1 million people, 1 in 250 in the United States in 2015, are living with aphasia. There are 180,000 new cases annually. There are …

- Aphasia – NIDCD – NIH — Most people who have aphasia are middle-aged or older, but anyone can develop it, including young children. About 2 million people in the United …

- Aphasia Following Acquired Brain Injury – Centre for Neuro Skills — It is estimated that 20% to 40% of individuals diagnosed with stroke have aphasia; the incidence of aphasia following TBI is between 2% to 32%. Despite the …

Legal Disclaimers & Brand Notices

The content of this article is provided for informational purposes only. It is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment from a qualified healthcare provider, such as a certified Speech-Language Pathologist (SLP) or physician. Always seek the advice of your SLP or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition or therapeutic strategy.

Reliance on any information provided in this article is solely at your own risk. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read here.

All product names, logos, and brands mentioned are the property of their respective owners.