Broca’s and Wernicke’s aphasia are two common post-stroke language disorders with distinct patterns: one affects speech production, the other comprehension. This article compares their causes, symptoms, and everyday impacts, then offers practical, evidence-informed home practice ideas and caregiver strategies for people living with aphasia after stroke or brain injury in the USA to support communication, memory, and connection at home.

How Broca’s and Wernicke’s Aphasia Differ Anatomically and Clinically

Clinical Definitions of Broca and Wernicke Aphasia

Broca’s aphasia is a nonfluent language disorder. It stems from damage to the frontal parts of the brain. People with this condition struggle to produce speech. Their sentences are often short. They leave out small words like “is” or “the.” This creates a telegraphic style of speaking. While speaking is hard, understanding others is usually a strength. This type is also known as expressive aphasia.

Wernicke’s aphasia is a fluent language disorder. It results from damage to the temporal lobe. Unlike the nonfluent type, speech flows easily. The rhythm and rate sound normal. However, the actual words often make no sense. People might use made-up words or substitute one word for another. This is called jargon or word salad. A major challenge here is comprehension. People with Wernicke’s aphasia have a hard time understanding spoken and written language. They are often unaware that their own speech does not make sense. This is called receptive aphasia.

Anatomical Locations and Brain Networks

The classical view links these disorders to specific spots. Broca’s aphasia is tied to the left inferior frontal gyrus. This is often called Brodmann areas 44 and 45. Wernicke’s aphasia is linked to the posterior superior temporal gyrus. This is Brodmann area 22. These areas are usually in the left hemisphere. For over 95 percent of right-handed people, language is on the left. For about 60 percent of left-handed people, it is also on the left.

Modern science shows the picture is more complex. Aphasia is not just about one spot. It involves networks. Recent data from Frontiers shows that Broca’s aphasia involves a broad network of cortical and subcortical regions. Lesion size matters a lot. A small injury might cause mild symptoms. A large injury that covers more of the network causes severe deficits. Researchers use voxel overlap to study this. In many Broca’s cases, there is a 52.9 percent overlap in regions that control tongue movements. There is a 21 percent overlap in regions for the larynx. This explains why the physical act of talking is so difficult. Wernicke’s aphasia often involves the ventral stream of the brain. This pathway is responsible for attaching meaning to sounds.

Comparing Clinical Presentations

The differences between these two types are visible in daily communication. We can compare them across several categories.

| Feature | Broca’s Aphasia | Wernicke’s Aphasia |

|---|---|---|

| Speech Fluency | Nonfluent and halting | Fluent and effortless |

| Sentence Structure | Agrammatic and short | Grammatical but nonsensical |

| Comprehension | Relatively good | Poor |

| Repetition | Impaired | Impaired |

| Naming | Significant struggle | Frequent errors and jargon |

| Awareness of Errors | High awareness | Low awareness |

Reading and writing patterns also differ. People with Broca’s aphasia might read okay but struggle to write. Their writing often mirrors their speech. It is sparse and effortful. People with Wernicke’s aphasia usually have impaired reading and writing. Their writing might be fluent but contain the same nonsense words found in their speech.

Associated Motor and Cognitive Deficits

Broca’s aphasia often comes with physical symptoms. The frontal lobe is near the motor cortex. Because of this, right-sided weakness or paralysis is common. Many people also have apraxia of speech. This is a problem with motor planning. The brain knows the word but cannot tell the mouth how to move. Dysarthria is another possibility. This is a weakness in the muscles used for speech. These issues add to the frustration of the speaker.

Wernicke’s aphasia rarely involves paralysis. Instead, other cognitive or sensory issues may appear. Visual field deficits are common. Some people experience acalculia. This is a difficulty with math and numbers. Agraphia is also frequent. Because they lack awareness of their errors, people with Wernicke’s may not feel the same immediate frustration as those with Broca’s. However, the lack of connection with others can lead to isolation.

Prevalence and Onset After Injury

Stroke is the leading cause of aphasia in the United States. About 795,000 strokes happen every year. Between 25 and 40 percent of survivors develop aphasia. This results in roughly 180,000 new cases annually. The risk changes with age. For people under 65, the incidence is about 15 percent. For those over 85, it is 43 percent. Traumatic brain injury and brain tumors also cause these disorders. Tumor-related aphasia occurs in 30 to 50 percent of patients.

The onset is usually sudden after a stroke. Broca’s aphasia often follows a blockage in the superior division of the middle cerebral artery. Wernicke’s aphasia usually follows a blockage in the posteroinferior branch. Recovery follows a specific timeline. Most improvement happens in the first two to three months. It typically peaks at six months. After six months, the rate of recovery often slows down. Broca’s aphasia generally has a better recovery outlook than Wernicke’s aphasia.

The Necessity of Formal Assessment

A formal assessment by a Speech-Language Pathologist is required for an accurate diagnosis. They use standardized tools to measure the type and severity of the condition. The Western Aphasia Battery-Revised is a common choice. It provides an Aphasia Quotient to track progress over time. The Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination looks at six dimensions of fluency. These include melodic line and phrase length. For naming issues, the Boston Naming Test is the standard tool. These assessments help create a targeted plan for home practice. Organizations like the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association and the National Aphasia Association provide resources for families. Understanding the specific breakdown in communication is the first step toward recovery.

Recognizing Symptoms and Daily Life Impact

Living with aphasia means the most basic parts of a day become hurdles. When you are at home, these challenges show up in the kitchen, at the mailbox, or during a quick phone call. For someone with Broca’s aphasia, the struggle is visible on their face. They know exactly what they want to say, but the words feel stuck. In a conversation, they might only manage to say “Water” or “Go store.” This telegraphic style leaves out the small words that glue sentences together. On a phone call, the silence can be heavy. They might take a long time to answer a simple question, which often leads the person on the other end to hang up or start talking over them. This creates a massive amount of frustration. Many people with Broca’s aphasia deal with depression because they are fully aware of their mistakes. They hear the wrong word come out and they feel the weight of every missed connection.

In contrast, Wernicke’s aphasia looks very different in a daily routine. A person might talk at a normal speed with a natural rhythm, but the words do not make sense. They might use “word salad” where real words are mixed with made up ones. When they are following a recipe, they might read the steps out loud perfectly but then fail to actually do the task. This happens because their brain is not processing the meaning of the language. They might put the flour in the sink instead of the bowl because the instruction did not click. Reading mail is equally difficult. They might see a bill and think it is a greeting card. Unlike those with Broca’s, people with Wernicke’s are often unaware that they are not making sense. This lack of awareness is called anosognosia. It can lead to social isolation because friends and family struggle to maintain a coherent dialogue.

Safety is a major concern for both types, especially regarding medication management. A person with Broca’s might understand the bottle says to take two pills at night, but they cannot tell their caregiver if they feel a side effect. A person with Wernicke’s might read the label and completely misunderstand the dosage. They might take too much or skip a dose because the words on the bottle do not translate into a clear action in their mind. Caregivers carry a heavy burden here. They have to become detectives. They must watch for physical cues or look for errors in tasks that used to be automatic. This constant monitoring leads to high levels of stress and exhaustion for the family.

Caregivers can look for specific pointers to understand how the aphasia is changing. One simple test is checking if the person can follow a one step command like “Point to the door.” If they can do that, try a two step command like “Pick up the pen and put it on the book.” People with Wernicke’s often fail at the two step level because their auditory processing breaks down. You should also watch for word finding frequency. Does the person struggle with every third word, or just occasionally? Note the types of errors. Are they using the wrong word that sounds similar, like “cat” instead of “cap”? Or are they using a word in the same category, like “apple” instead of “orange”? These details are vital for the speech language pathologist.

There are red flags that require an immediate medical or therapy review. If you notice a sudden drop in comprehension or if the person becomes much more confused than usual, call a doctor. New physical symptoms like weakness on one side or a drooping face are also emergencies. In the context of therapy, a red flag is a total plateau where no progress is made for over a month despite consistent practice.

Recovery trajectories vary based on the severity of the initial brain injury. Most significant recovery happens in the first two to three months after a stroke. It usually peaks around the six month mark. Research shows that people with Broca’s aphasia often have a better recovery path than those with global aphasia. Those with Wernicke’s aphasia may face a longer road because the comprehension deficit makes it harder to participate in certain types of therapy. However, intensity matters. Studies have shown that intensive therapy, such as twenty hours over two weeks, can lead to significant improvements even in chronic cases.

| Daily Task | Broca’s Aphasia Impact | Wernicke’s Aphasia Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Phone Calls | Long pauses and one word answers. | Fluent speech that does not answer the question. |

| Reading Mail | Slow reading but usually understands the point. | Can read words aloud but misses the meaning. |

| Social Events | Withdrawal due to the effort of speaking. | Talking a lot but others cannot follow the logic. |

| Medication | Knows what to take but cannot ask for help. | High risk of taking the wrong dose due to confusion. |

Understanding these daily impacts helps in setting realistic goals. It is not just about “fixing” speech. It is about making sure the person can safely navigate their home and stay connected to the people they love. Whether it is using a picture board for a person with Broca’s or using written keywords to help someone with Wernicke’s, the focus is on functional communication. Every small win in a daily task is a step toward a better quality of life. For more detailed information on the clinical definitions of these conditions, you can refer to the ASHA practice portal on aphasia. This resource provides a deep look at how these language disorders are classified and treated in the US.

Evidence-Informed Home Practice Strategies and Activities

Building a home practice routine is a vital step in recovery. Research shows that the brain has a remarkable ability to reorganize itself after a stroke or injury. This process is most active in the first six months. Most people see the biggest gains during this window. However, progress can continue for years with the right approach. Practice at home should be consistent and focused on the specific type of aphasia a person has.

Home Practice for Broca’s Aphasia

Broca’s aphasia makes it hard to turn thoughts into spoken words. The goal of home practice is to rebuild the motor patterns for speech and improve the flow of sentences. Since comprehension is usually good, these activities focus on expression.

Script Training

Pick three or four phrases that are used every day. These might include a coffee order or a greeting for a neighbor. Practice these exact phrases for ten minutes every day. Start by saying the phrase together with a partner. Then have the partner mouth the words while the person with aphasia speaks. Finally, try to say the phrase alone. This builds muscle memory in the speech centers of the brain.

Melodic Intonation Therapy Basics

Many people who struggle to speak can still sing. This technique uses the right side of the brain to help the left side. Choose a simple two-syllable phrase like “Water.” Hum the word in a sing-song rhythm while tapping the person’s left hand on a table. Gradually move from humming to singing the actual words. Over time, fade the singing until it becomes regular speech. This is a powerful tool for those with severe non-fluent aphasia.

Sentence Completion and Motor Cueing

Use familiar phrases to trigger speech. A partner can start a sentence like “I want to eat a…” and let the person fill in the blank. If the word is stuck, use motor cues. This means showing the person how to position their mouth for the first sound. For the word “apple,” open your mouth wide. For “paper,” press your lips together. These visual prompts help the brain find the right motor plan.

Home Practice for Wernicke’s Aphasia

Wernicke’s aphasia affects how a person understands language. Speech might be fast and fluent, but the words often do not make sense. Practice here focuses on listening and connecting words to their meanings. You can find more about these methods through Tactus Therapy resources.

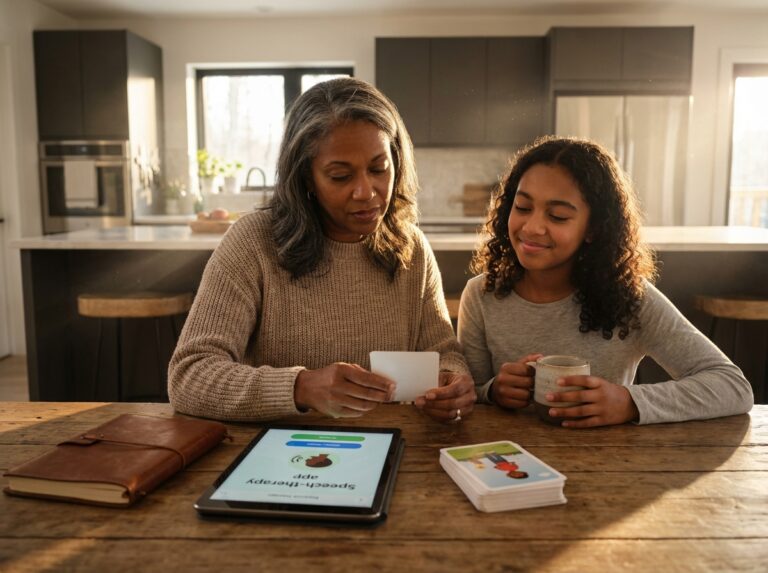

Matching and Sorting Exercises

Use a deck of cards or printed photos of common objects. Ask the person to sort them into categories like “things we eat” and “things we wear.” This forces the brain to process the meaning of the image. You can also lay out three photos and ask the person to point to the “dog.” If they choose the wrong one, gently point to the correct photo and say the word clearly.

Semantic Feature Analysis for Receptive Deficits

This activity helps strengthen the mental map of a word. Place a picture of an object in the center of a piece of paper. Draw lines to different categories like “What is it used for?” or “Where do you find it?” Even if the person cannot say the answers, have them point to icons or written words that describe the object. This reinforces the concept behind the word.

Using Written Keywords

People with Wernicke’s aphasia often understand written words better than spoken ones. When you have a conversation, write down the main topic in large capital letters. If you are talking about the weather, write “WEATHER” on a notepad. This acts as an anchor. It helps the person stay focused on the topic even if they do not understand every spoken word.

Session Structure and Frequency

The brain learns best through distributed practice. This means doing short sessions often rather than one long session once a week. Evidence suggests that intensity matters. Some studies show that twenty hours of therapy over two weeks can lead to significant improvement. At home, aim for the following schedule.

| Routine Component | Duration | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Warm-up (Singing or humming) | 5 minutes | Daily |

| Core Task (Scripts or Matching) | 15 minutes | 3 to 5 times a week |

| Cognitive Break | 5 minutes | As needed |

| Functional Task (Phone call or list) | 10 minutes | Daily |

Technology and Multisensory Support

Apps can provide extra practice when a therapist is not available. Constant Therapy and Tactus Therapy are two high-quality options used in the USA. These apps adjust the difficulty based on how well the person is doing. For those with severe deficits, Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) tools are helpful. This might be a simple board with pictures of “hungry,” “thirsty,” or “bathroom.” It reduces frustration by providing a way to communicate basic needs without relying on speech.

Memory and cognition also need support. Use a large wall calendar for daily routines. Spaced retrieval is a technique where you ask the person to remember a piece of information, like a room number, at increasing intervals. Ask them, then ask again one minute later, then five minutes later. This builds functional memory.

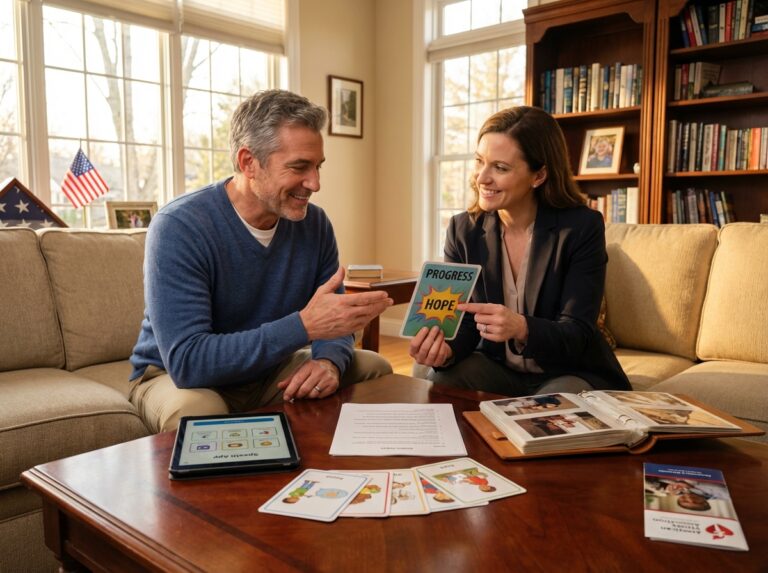

Caregiver Coaching Tips

The way a partner communicates can change the success of home practice. Simplify your input. Use short sentences and avoid complex grammar. Pace your speech so there are clear gaps between sentences. This gives the brain time to process the information. Always provide choices. Instead of asking “What do you want for lunch?” ask “Do you want soup or a sandwich?” while holding up the items or photos. Reinforce every success, even if the word is not perfect. Motivation is a huge factor in long-term recovery. For more professional guidance, you can visit the ASHA website to find local clinicians and training materials. Organizations like the National Aphasia Association also offer community groups that provide emotional support for both the person and the caregiver. Safety should always come first. If you notice a sudden drop in communication or new physical weakness, seek medical review immediately. Setting small, measurable goals helps keep the momentum going during the long road of recovery.

Frequently Asked Questions About Living with Aphasia

What is the difference between Broca’s and Wernicke’s aphasia in simple terms?

Broca’s aphasia is often called non-fluent aphasia, while Wernicke’s is fluent aphasia. The key difference is in the flow of speech and the level of comprehension.

Example. Someone with Broca’s might say “Walk dog” instead of “I am taking the dog for a walk.” Someone with Wernicke’s might say “The blue sky is running the table” with perfect rhythm.

Immediate action. Observe if the struggle is with finding words or understanding them. This helps your speech therapist create the right plan. You can find more details on these types at StatPearls NCBI.

Can aphasia improve and what influences recovery?

Yes. Language skills can improve for years after a brain injury. Factors like the size of the brain lesion and the intensity of therapy play a big role. Motivation and consistent home practice are vital. Research shows that intensive practice, such as 20 hours over two weeks, can lead to significant gains even in chronic cases.

Example. A person might start with single words and move to full sentences over several months of daily practice.

Immediate action. Set small, measurable goals for each week. Track progress using a simple journal to stay motivated.

When should I call an SLP or seek medical review?

You should consult a Speech-Language Pathologist (SLP) immediately after a diagnosis. They provide the roadmap for recovery. Seek a medical review if you notice sudden changes. If comprehension gets worse or new physical symptoms appear, call a doctor. If home practice feels stagnant for over a month, an SLP can adjust the strategy.

Example. If a person who could follow one-step directions suddenly cannot, that is a red flag.

Immediate action. Use the ASHA Pro-Find tool to locate a certified therapist in your area.

What home activities are safe and useful?

Safe activities focus on low-stress communication. For Broca’s aphasia, try script training for common phrases like ordering coffee. For Wernicke’s aphasia, matching pictures to written words helps anchor meaning. Sorting household items by category is also effective. These tasks do not require special equipment and can be done during daily routines.

Example. Labeling kitchen cabinets with large print words helps connect objects to their names.

Immediate action. Choose two activities from the previous chapter and try them for 15 minutes today.

How can family members support conversations without causing frustration?

Patience is the most important tool. Give the person extra time to respond. Do not finish their sentences unless they ask for help. Use short sentences and simple words. Visual aids like gestures or drawing can bridge gaps. Avoid correcting every mistake. Focus on the message rather than perfect grammar.

Example. Instead of saying “That is not the right word,” try “I think you mean the car. Is that right?”

Immediate action. Practice the “wait ten seconds” rule before offering a word or prompt.

What technology or apps are most helpful for practice and communication?

Many apps are designed specifically for aphasia recovery in the USA. Constant Therapy and Tactus Therapy are highly recommended. These tools offer exercises for naming, comprehension, and reading. They often provide data that you can share with your SLP. High-quality teletherapy platforms also allow for professional sessions from home.

Example. Using a naming app for 10 minutes a day can improve word retrieval for common objects.

Immediate action. Download a trial version of a therapy app to see which interface feels most comfortable.

How to manage emotional changes and social isolation?

Aphasia often leads to frustration or depression. This is especially common in Broca’s aphasia because the person is aware of their errors. Social isolation happens when people avoid groups due to communication fears. Joining a support group is a powerful way to reconnect. The National Aphasia Association offers many virtual resources for families.

Example. Attending a local stroke survivor meet-up can provide a sense of community.

Immediate action. Visit the National Aphasia Association website to find a local or online support group.

When is alternative or augmentative communication appropriate?

Alternative or augmentative communication (AAC) is useful when verbal speech is not enough for daily needs. This can be a simple picture board or a high-tech tablet app. It is not a sign of giving up on speech. Instead, it reduces frustration and helps the person stay involved in life. An SLP can help determine if AAC is the right fit.

Example. Using a tablet to show a picture of a “glass of water” when the word will not come out.

Immediate action. Ask your SLP for an AAC evaluation if basic needs are not being met through speech alone.

Key Resources for Families

Navigating life after a brain injury requires reliable information. These organizations provide evidence-based guidance and support networks across the United States.

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA). Offers a directory of certified professionals and clinical information.

- National Aphasia Association (NAA). Provides educational materials and a list of local support groups.

- Tactus Therapy. Offers specialized guides for Wernicke’s therapy and home practice apps.

Conclusions and Next Steps for Home Practice

Prioritizing your goals

Start with goals that impact safety and basic needs. It is tempting to want to return to long conversations immediately. However, being able to ask for medication or explain a pain level is more urgent. Sit down with your family and list three things that would make daily life easier. This might be using the phone or ordering a meal. Once safety is covered, move to social goals. Connection is vital for mental health. Choose activities that allow for success. If a task is too hard, it leads to burnout. If it is too easy, the brain does not learn.

When to involve a professional

A speech language pathologist is a necessary partner in this process. They provide formal assessments like the Western Aphasia Battery. These tests give you a baseline score to track progress. You should seek a professional if you notice a sudden decline in communication. You should also call an SLP if home practice feels stuck. In the United States, many therapists now offer services through telehealth. This is a great option if you have transportation issues or live in a rural area. Professional guidance ensures you are doing the right exercises for your specific type of aphasia. You can find more details on clinical types through StatPearls.

Simple daily routines for the first week

Consistency matters more than intensity when you first start. Aim for short sessions of five to thirty minutes. Do these three to five times a week. This is called distributed practice. For the first week, keep things low pressure. If you have Broca’s aphasia, try naming five objects in the kitchen every morning. If you have Wernicke’s aphasia, practice following one step directions. You could ask a partner to give you a simple command like “point to the door.” Use visual aids like pictures or gestures to help. Keep a simple log of what you did each day.

How to measure your progress

Progress in aphasia recovery is often slow. It is measured in small wins rather than sudden leaps. Most recovery happens in the first six months after a stroke. Improvement can continue for years, but the pace changes. Use a notebook to track how many times a person successfully finds a word without help. You can also track how long a conversation lasts before frustration sets in. Do not compare today to life before the injury. Compare today to last month. Small improvements in clarity or understanding are major victories.

The role of caregiver support

Caregivers carry a heavy load. It is important to stay patient and keep expectations realistic. Avoid the urge to finish sentences for the person with aphasia. Giving them time to process and respond is a form of therapy. If frustration gets too high, take a break. Communication should not feel like a battle. Use reputable resources for support. The National Aphasia Association offers materials for home use. Staying connected with other families going through the same thing can reduce the feeling of isolation.

Practical first actions checklist

Schedule an SLP assessment

Contact a local clinic or check your insurance for telehealth options to get a professional evaluation.

Choose two home activities

Pick two simple tasks like naming household items or practicing basic requests to do this week.

Set one small goal

Identify one specific thing you want to achieve by next Sunday, such as saying a family member’s name clearly.

Create a practice space

Find a quiet spot in the house without the TV or radio on to minimize distractions during your sessions.

Recovery is a marathon. There will be good days and difficult ones. Focus on the connection you share with your loved ones. Language is just one way we relate to each other. Even when words are hard to find, your presence and effort matter. Keep practicing and stay encouraged.

Sources

- The neuroanatomy of Broca's aphasia – Frontiers — Recent evidence suggests that the neuroanatomy of Broca's aphasia is far more complex, implicating a broader network of cortical and subcortical regions.

- Aphasia – StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf – NIH — Clinically, common types of aphasia include Broca and Wernicke aphasia … Network-based statistics distinguish anomic and Broca aphasia. ArXiv …

- Aphasia: Types, Causes, Prevalence, and Treatment Options — Broca's aphasia can occur due to damage to the brain's frontal lobe. … Also known as fluent aphasia, people having Wernicke's aphasia can …

- Wernicke Aphasia – StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf – NIH — Unlike Broca aphasia, patients with WA speak with normal fluency and prosody and follow grammatical rules with normal sentence structure.

- Treatment of Wernicke's Aphasia (TWA) Guide for Speech Therapy — Six of the nine subjects had Wernicke's aphasia. After more than 20 hours of therapy in 2 weeks, 2/3rds of the subjects improved significantly on measures of …

- Aphasia – ASHA — Aphasia is an acquired neurogenic language disorder resulting from brain injury. Aphasia may affect receptive and expressive language.

- The Fast Facts on Aphasia – Universal Health Fellowship — Broca's Aphasia is associated with right-sided paralysis and weakness. Comprehensive (Wernicke's) Aphasia. Those with Wernicke's Aphasia tend …

- Comparison of Large Language Model with Aphasia – Watanabe — In particular, for Wernicke's aphasia, we also have to clarify behavioral and linguistic differences between its symptoms and typical …

- [PDF] Broca's vs. Wernicke's aphasia – Iowa Research Online — As previously discussed, compared to people with Wernicke's aphasia, those with Broca's aphasia tend to produce more sparse and effortful verbal output, while …

Legal Disclaimers & Brand Notices

The information provided in this article is for informational and educational purposes only and does not constitute professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of a physician, speech-language pathologist, or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition or recovery plan. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read in this content.

All product names, logos, and brands mentioned in this text are the property of their respective owners. All company, product, and service names used in this article are for identification purposes only. Use of these names, logos, and brands does not imply endorsement.